Newly Published Article Explains How Physicians Would Benefit from Understanding the Role of Microbiology in Disease and Human Health

Could the cure for cancer, obesity, and other major health problems be in your gut?

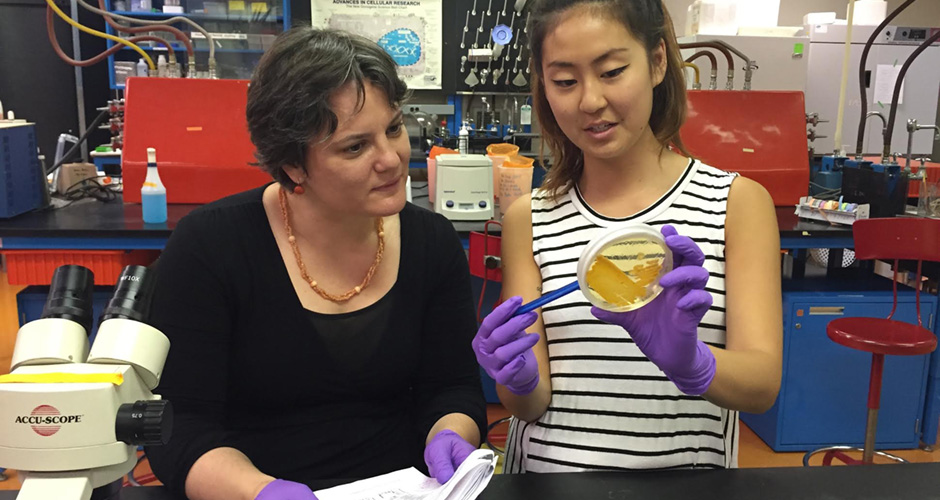

"Yes. The two and a half pounds of microbes living in and on our bodies—most of them in our gut—could have the power to heal us," said Vanja Klepac-Ceraj, assistant professor of biological sciences. Klepac-Ceraj is the corresponding author of a review article titled "Microbiology and Ecology Are Vitally Important to Premedical Curricula," recently published in the online journal Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health. She and her co-authors—including Wellesley students Serry Park '16 and Rebecca J. Rubinstein '15—believe an understanding of microbiology would change the way physicians diagnose and treat many diseases.

"Our bodies harbor hundreds to thousands of different species of microbes, and these microbes do a lot for us; they help us digest our food, synthesize vitamins we cannot make ourselves, and protect us from harmful microbes that could make us sick," said Klepac-Ceraj. "In recognition of the complex relationship that exists between the human body and its resident microbiota, our manuscript uses four examples from the biomedical literature to argue that a knowledge of microbiology and ecology can lead to new ways to keep us healthy, or help us get healthy."

The first example has received a great deal of media attention in recent years: the overuse of antibiotics, which leads to antibiotic resistance and the proliferation of infections. "Understanding this can help us use antibiotics most effectively to combat infectious diseases and/or slow down the emergence of antibiotic resistance," said Klepac-Ceraj.

The public is less familiar with the prominent role microbes play in obesity, metabolic disorders, and inflammatory diseases. Cancer, a complex and multifactorial disease, may also be influenced by microbiology, because microbes affect how dietary nutrients are metabolized and whether they suppress inflammation and carcinogens or cause DNA damage. Research suggests that the microbiome may even play a role in modulating behavior, cognition, and mood.

"Imagine going to a doctor and the doctor taking a snapshot of your gut microbiome. Then she or he would be able to prescribe a diet or a pill with microbes that would modify the microbiome back to a state associated with health," said Klepac-Ceraj.

That doesn’t happen yet, she explained, because the field is so new and complex. "We still do not know enough about how particular microbes affect our health or digestion to design a targeted treatment," she said. "Nor have we learned the best way to prepare physicians for the medicine of the future."

In medical school, microbiology is often taught in the context of pathogenesis, she said, which may lead many health professionals to approach disease through the lens of mammalian anatomy and physiology, ignoring the physiology and cell biology of our microbial inhabitants.

Furthermore, medical schools do not require microbiology for admission, unlike many veterinary schools or nursing schools. (The required biology coursework is mostly centered around genetics and cell biology with an emphasis on human biology.) "The knowledge of microbiology or ecology is not even required for the MCAT (Medical College Admission Test)," Klepac-Ceraj said.

Identifying this oversight was one of many contributions Park and Rebecca J. Rubinstein, both biology majors, made to the article. Both students researched and wrote sections of the paper, and were involved in all aspects of the editing process.

"Writing this paper was a great opportunity for me to learn about the fascinating current research on the gut microbiome," said Rubenstein, who is currently working in the Dominican Republic on a research study of the chikungunya virus.

Park agrees. "I never even considered pursuing microbiology before coming to Wellesley, and now I can’t see life and medicine without also seeing the impact of microbes,” she said. “The entire process not only taught me how to write scientifically, but really allowed me to think critically, which I think has made me a better student, scientist, and, hopefully one day, doctor."