Faculty Provide Lessons from History by Looking Back to the Attack on Pearl Harbor, 75 Years Ago

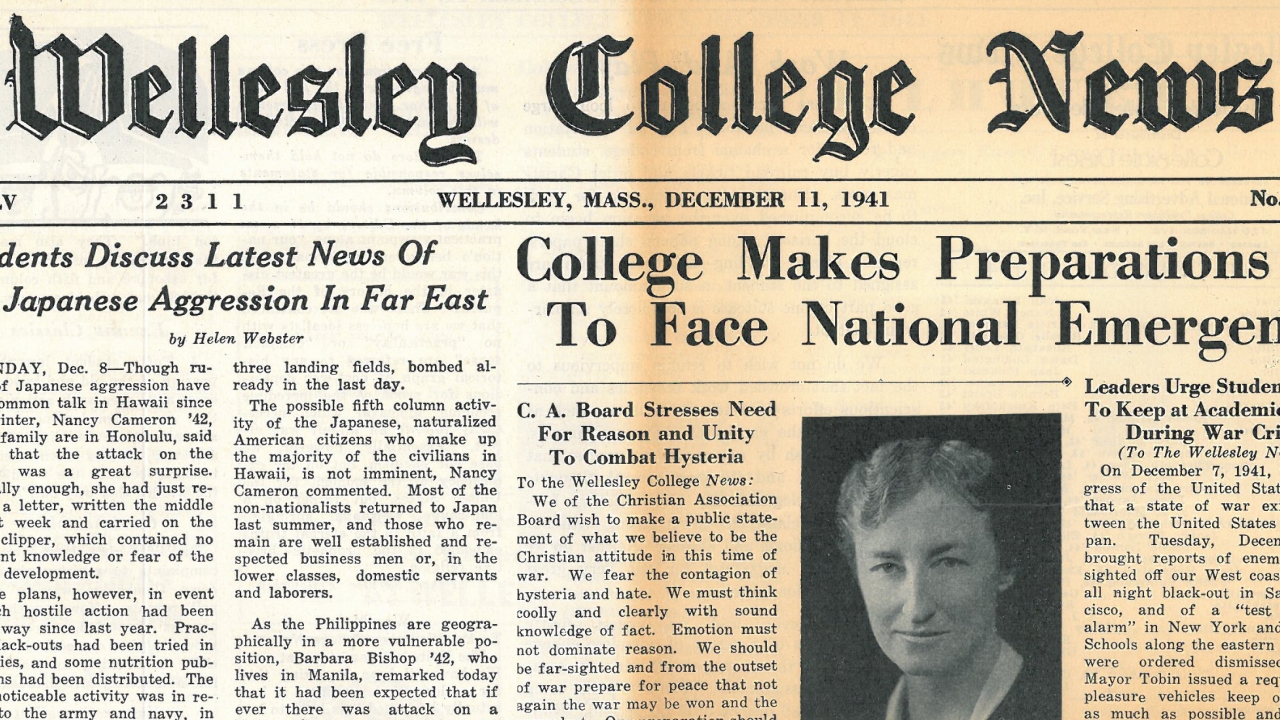

Seventy-five years ago, the Wellesley News front page read: “College Makes Preparations to Face National Emergency.” The country was reeling from the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Wellesley’s campus was no different. During the past week, the world has been reflecting on the lessons we can glean from that pivotal moment in history. Three Wellesley professors—of political science, history, and religion—offer their thoughts and reflections on the ways looking back can give us clarity as we consider the global complexities of present day. Their comments range from insights on world events, to a teachable moment about why we study history, to a personal narrative.

Marking the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor is especially unique this year because Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan has promised to visit Pearl Harbor on December 26 and 27, 2016. He will be accompanied by President Barack Obama, who was the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima, in May 2016—bold steps for the two leaders to lead the spirit of reconciliation after violent combat and mutual dehumanization through the U.S. atomic bombs blasted over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. But the urgency of reconciliation for Japan is with other Asian nations, who were brutalized during Japan’s imperial war in the Pacific and the colonization of some Asian societies. And the urgency for the United States is to reconcile with Asian nations, including Japan, through a recommitment to democracy, the fight against racism, and hyper-nationalism. In the 1930s, Japan lacked a democracy and was fueled by racist nationalism into imperialist adventurism and war. Remembering the past is essential as a new U.S. president and his team take on the very weighty political and moral mantle of leadership.

Y. Tak Matsusaka, professor of history, wrote:

Think about Japan’s place in the world and its relationship with America today. Then reflect on the fact that 75 years ago, the same country attacked Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States. The need to wrap our heads around such mind-boggling changes is the reason why we study history.

T. James Kodera, professor of religion, wrote:

My father, born in Manchuria, China, during Japan’s occupation there, fought for Japan. Since he was a great athlete, the last national champion of tennis before the outbreak of the war in 1941, he was drafted in the last minute. In the last-ditch effort by Japan, he was flown to the Philippines. He, together with one other, was ordered to return promptly back to Japan to carry a letter written by the commander of the Japanese military in the Philippines. The letter turned out to be by General Yamamoto, urging the emperor to surrender. That is why he and his comrade survived the war; the rest all perished.

Another personal history: On my mother’s side, my family comes from Nagasaki. Many of her extended family members and her classmates died on the day the second atomic bomb was dropped in Nagasaki, on August 9, 1945. My mother, luckily, was in Kobe, where she was attending college and living with her mother. Today, Hiroshima has come to be known as the “City of Anger,” [and] Nagasaki as the “City of Prayer,” largely because of the effort by Takashi Paul Nagai, a radiologist, a survivor of the bomb, if only for six years, and a convert to Roman Catholicism. He regarded the bomb dropped in Nagasaki as God’s plan for Nagasaki to become the starting point of a peace movement without nuclear arms. We think of Nagasaki simply as the second city where the atomic bombs were dropped. When we visit the two cities, we will witness two very different remembrances of the bomb and outlook on the future.

Given my family experience during World War II, I chose to become a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1979 as a conscientious objector, renouncing my Japanese citizenship. In the process, I was blamed for bombing Pearl Harbor. [As a conscientious objector], I pledged to do whatever I can to prevent wars. As a student of religion, I am well aware that religious convictions foster and justify war, while they can also propel us to eliminate wars. Of the two, the former is a great [deal] more common in human history. I try to do my small part in urging students at Wellesley to do their part, too.”