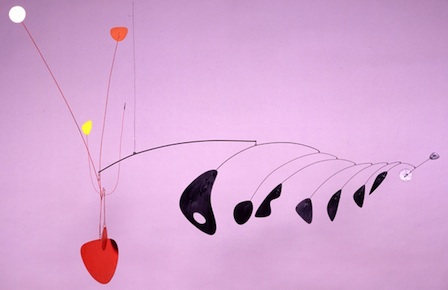

Study for Lobster Trap and Fish Tail

Considered a major breakthrough in modern sculpture, Alexander Calder’s most notable mode, the mobile, acts as evidence of his flair for humor and whimsy. Capturing the motion of the sea, Study for Lobster Trap and Fish Tail floats above the museum space, quietly dancing about the viewer below. Turning in its place, the mobile evokes the soft undulations of the ocean floor. The colors and forms of the sculpture further this evocation of marine life, creating figural allusions to its namesake – a lobster and a fish tail. Its motion, sensitive to even the softest blow, resembles the response of the sea to a crossing boat, the activation of the sculpture’s forms echoing the rhythmic stirring of gentle ocean waves. The ability to shape and follow the movements of the mobile is especially delightful for the viewer, rousing a childlike fascination as one watches its frame shake and wiggle. Enhancing the interaction between the sculpture and the individual, Calder separates his works from the truly ‘grounded’ practices of traditional sculpture, continuing his interest in the play between natural and mechanical movement.

Calder experimented with kinetic forms in his early creation, Cirque Calder. A miniature circus, Cirque Calder is comprised of various characters, namely ringmasters, gymnasts, and animals. Maneuvered through the arena by Calder, the wire creatures were lifted and placed in their respective acts. Though controlled by both Calder and the mechanisms of his various contraptions, the figures were still subject to natural movement; sometimes falling and moving in ways that he had not expected. In a similar sense, the motion of Study for Lobster Trap and Fish Tail is also the result of the natural and the mechanical. Conjuring the acrobatic balance and precarious movement of a tightrope walker, the mobile hangs above the audience of the gallery space, as if referencing the performance of Cirque Calder’s small wire creatures. Purposely assembled to produce an opposition of horizontal and vertical arms, the duration and complexity of its chance movement would not exist without the mobile’s technical proficiency. Yet, it is not motorized. The mobile is just as reliant upon the soft breeze of the environment, or viewer, as its efficient construction. Without the two, the mobile would not fully realize its acrobatic balance and motion, nor would it engage the spectator, regardless of its position above a dining room table or in the gallery space of a museum.

This work is currently on view in the Dorothy Johnston Towne Gallery on the second floor of the museum.

Quinn Refer ’14

Curatorial Intern, Summer 2012