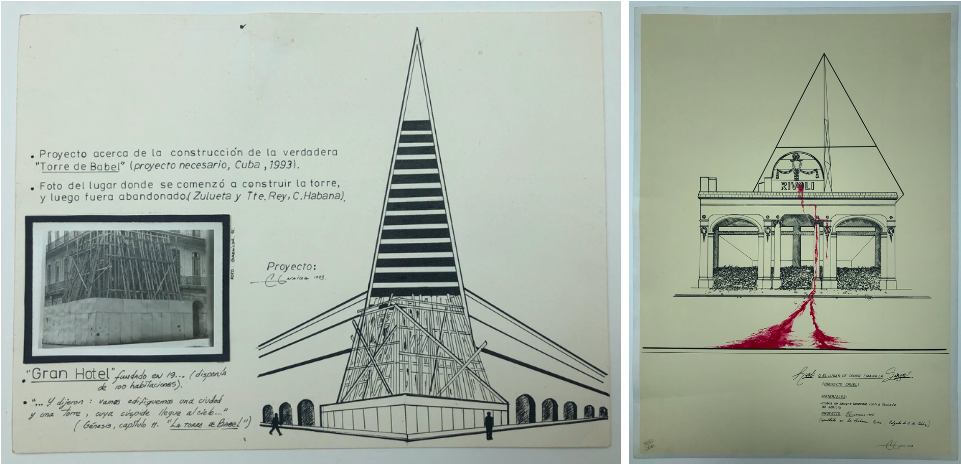

Construction Project Tower of Babel; Rivoli

Carlos Garaicoa, (b. 1967 Havana, Cuba), Proyecto acerca de la constuccione de la verdadera Torre de Babel (Project drawing for On the Construction of the Real Tower of Babel), 1993, Ink drawing with photograph (collage), Gift of the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino Gallery 2019.1241 (Left). Carlos Garaicoa (b. 1967 Havana, Cuba), Rivoli o el lugar de donde emana la sangre (proyecto cruel) (Rivoli, or the Place from Which the Blood Flows (Cruel Project)), 1994, Screenprint with watercolor, Gift of the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino Gallery 2019.1240 (Right)

The generous donation of two works by Carlos Garaicoa brings this influential Cuban artist into the collections of the Davis Museum for the first time. Born in Havana in 1967, Garaicoa currently lives and works in Madrid, and also maintains a studio in Havana. His work has been widely exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Biennale and Documenta 11 and 14, and is held in many significant collections, such as the Museum of Modern Art, the MFA Houston, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Garaicoa investigates the symbolic power of architecture—often, as in these two works, in Havana—and how the meanings of structures are shaped by the passage of time. Havana is marked by ruins: buildings from the pre-Revolutionary past that have disintegrated from neglect, as well as modernist projects left unfinished by the 1959 Revolution. For the artist, these modern ruins allow him to critique generally accepted modernist ideas concerning social and political utopias, as well as the political, economic, and social structures and policies that constantly change the urban landscape. Many of his works mimic the blueprints of the professionals he questions.

The unique collage On the Construction of the Real Tower of Babel (Proyecto acerca de la construcción de la verdadera Torre de Babel) includes a photograph showing part of the Gran Hotel, built in 1889, with one corner of the historic building supported by wooden beams to prevent collapse. In Garaicoa’s hands, the beams become the fictional foundation for a modern gleaming pyramidal tower that seems to have been abandoned by the Revolutionary government: such a project would have been absurd in the early 1990s. He refers to this unbuilt structure—shown in the drawing as if an architect’s sketch—as a new or “real” Tower of Babel, raising questions about communication in a place meant to house foreign tourists.