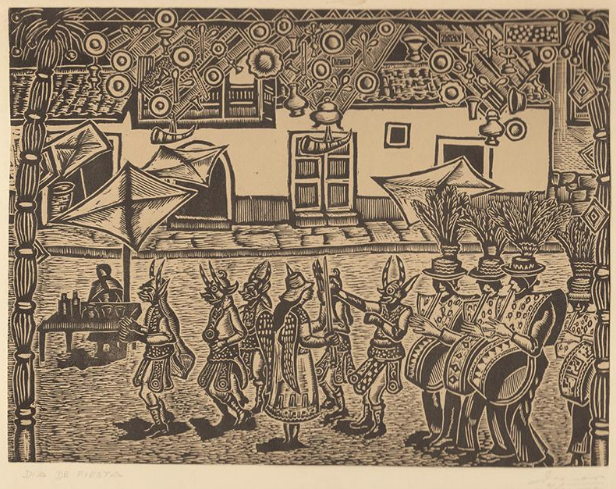

Día de Fiesta

Genaro Ibañez, Día de Fiesta, ca. 1940, Wood engraving, Museum purchase with funds provided by Wellesley College Friends of Art, 2015.18

Genaro Ibáñez was born in La Paz, Bolivia and studied in both Buenos Aires, Argentina and Madrid, Spain. In 1948, Ibanez became a professor and later director of graphic arts at the Escuela de Bellas Artes of La Paz. The school, founded in 1926, had appointed the artist Cecilio Guzmán de Rojas as the director in 1930. Guzmán de Rojas championed Indigenism, a style that many artists were exploring which embraced an romanticized version of Native culture in Latin America. While Ibáñez was both a painter and a printmaker, he was most praised for wood engravings of local architecture and Indigenist themes. Día de Fiesta shows a procession through the street, most likely around the time of Carnaval. The horned figures and the angel are characters from the “Danza de la Diablada” or dance of the devils. The dance, a hybrid of Spanish and Andean traditions, was originated in Boilvia in the late-seventeenth century by miners, who were mainly converted indigenous people. It enacts a battle between good and evil, in which the sword-wielding Archangel Michael represents Catholicism, while the caped Lucifer represents el Tío, a devil-like, pre-Columbian god who presides over the mines. The image might also refer to a ch’alla, a pre-Hispanic Andean ritual involving alcohol, colorful decorations, and offerings--sold by street vendors like the one in the image--that is held on the morning of the first day of Carnaval. The banner across the top of the image represents the type of decoration used in the ch’allas, and also most likely shows Andean objects.

The second set of men in the procession performs the “dance of quena quenas,” identifiable through them men’s quena flutes, wool hats, and jaguar-skin “caparazones,” or shell-like vests. This dance is not typically associated with Carnaval and is considered an autochthonous custom performed for agricultural ritual and, in some instances, as a war cry.

--Melina Mardueño ‘18, Summer Curatorial Intern