Gesture and Geometry

In postwar Latin America, as elsewhere, abstraction followed two simultaneous paths, one subjective and expressive, the other objective and analytical. Yet these were never entirely in opposition. Joaquín Torres-García and his students sought to combine the constructivist grid with evocative and mythical symbols, sometimes referring to the ancient past. Some artists were inspired by the Surrealists’ interest in biomorphic forms, or their embrace of automatism and “primitive” or children’s art as means to communicate deeper emotional truths. Later painters drew on an expressionist legacy to create powerful gestural abstractions, sometimes working outside the mainstream. Others emphasized control and rational analysis in geometric abstractions and kinetic works that built on a constructivist tradition. This multiplicity of trajectories is not at all contradictory. One of the great contributions of Latin American artists to the history of abstraction is their resistance to easy categorization, particularly evident in works where grids are softened by hand-drawn lines or where humor invades the empty fields of minimalism.

Alice Rahon (Chenecey-Buillon, France 1904 – 1987 Mexico City, Mexico), Boite à Musique I (Music Box I), 1944, Oil, sand, and ink on canvas, with artist’s frame, Museum purchase with funds provided by Wellesley College Friends of Art 2014.124

Music Box I is an early work by the French poet and painter Alice Rahon, one of the most important women affiliated with the international Surrealist movement. She took up residence in Mexico with her husband, artist Wolfgang Paalen, in 1939. Rahon’s experimental technique reveals an embrace of Surrealist theory: she covered the canvas with thin veils of oil paint, added a layer of powdered sand, and finally abraded and etched the surface. The playful imagery evokes the abstraction of free verse or musical notation, trapped by the deep frame, which was designed by the artist.

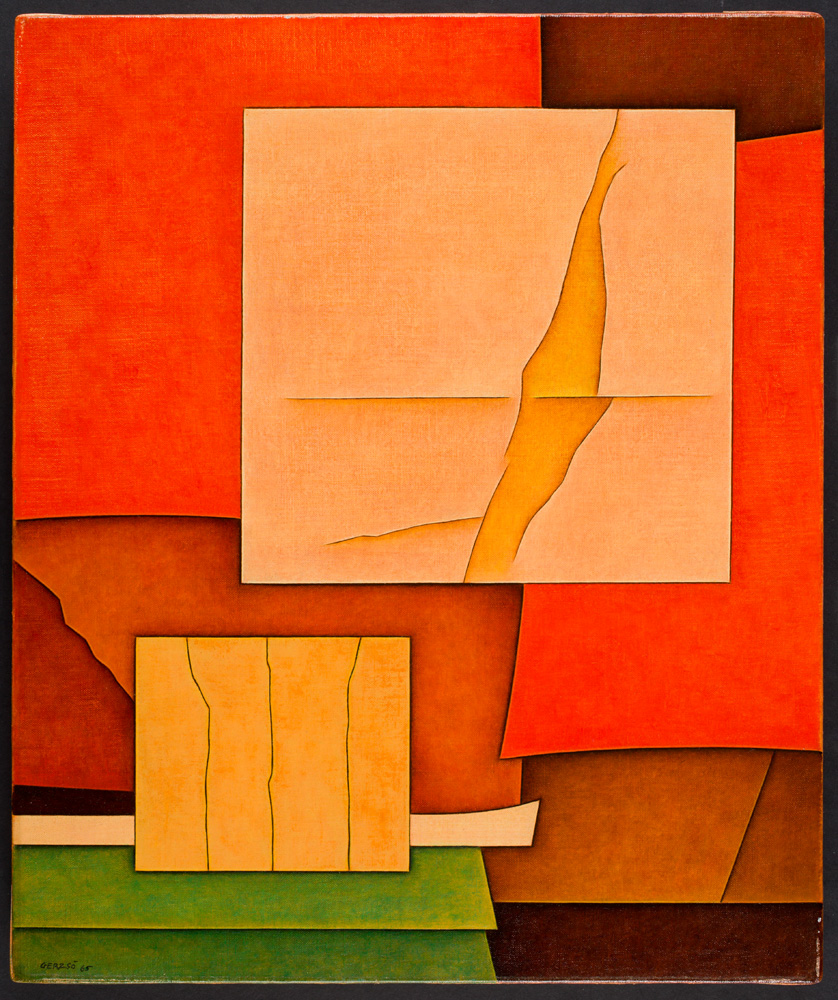

Gunther Gerzso (Mexico City, Mexico 1915 – 2000 Mexico City), Rojo y amarillo (Red and Yellow), 1965, Oil on canvas, Bequest of Dr. Ruth Boschwitz Benedict (Class of 1935) 1994.40. Courtesy of the artist’s estate, © John Michael Gerzso 2013.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, like abstract artists in many parts of the world, Gunther Gerzso turned to the forms and myths of the ancient past as a means of grappling with the mysteries of the human condition and its uncertain future. Later paintings, such as Red and Yellow, expand the artist’s richly colored, layered geometric planes. At a time when realism prevailed in Mexico, Gerzso was often framed as a foreigner: he may have adopted ancient Mesoamerican references as a way to challenge limited definitions of individual and national identity.

Olga Albizu (Ponce, Puerto Rico 1924 – 2005 New York, New York), Untitled, 1959, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, The Dorothy Johnston Towne (Class of 1923) Fund 2018.165. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Olga Albizu studied painting in Puerto Rico but did not embrace abstraction until she moved to New York, where she studied under Esteban Vicente and Hans Hoffman. Her alignment with abstract expressionism defies the notion of separate US and Latin American cultural discourses, but only recently has she been reclaimed as part of the history of US art. Unlike Lorenzo Homar and other Puerto Rican artists who fought cultural assimilation during the island’s transition to Commonwealth status, Albizu’s strong belief in creating an art separate from politics remained constant throughout her life.

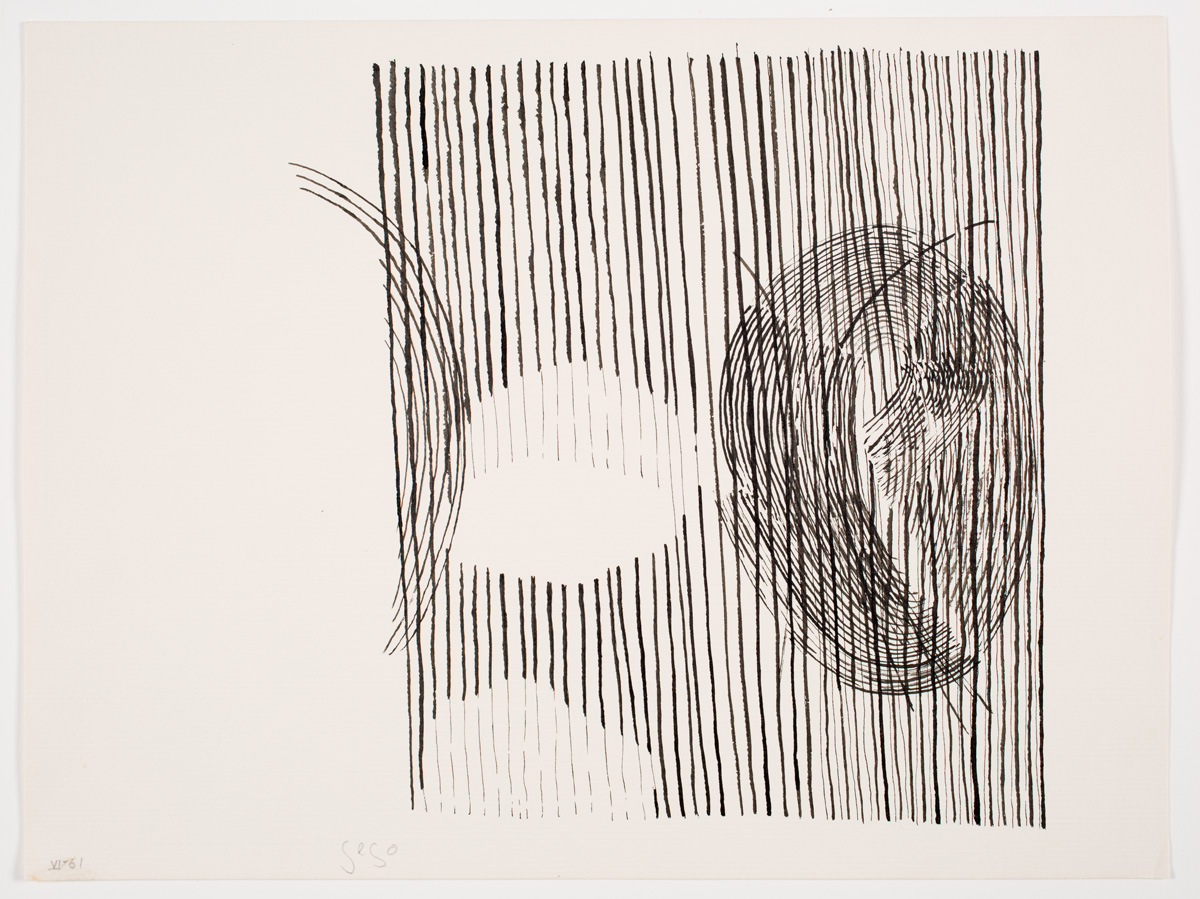

Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt) (Hamburg, Germany 1912 – 1994 Caracas, Venezuela), Untitled, 1961, Ink, Museum purchase with funds provided by Cecily E. Horton (Class of 1980) 2018.223. Courtesy of the artist's estate, © Fundación Gego.

The German-born Venezuelan sculptor Gego once declared, “There is no danger for me to get stuck, because with each line I draw, hundreds more wait to be drawn.” This drawing is typical of her two-dimensional work, in which she traces parallel lines by hand, creating a screen-matrix through which she weaves other lines to generate new forms. This textile-like approach, however, is hardly mathematical, for Gego delights in irregularity: the lines change in thickness, intersect at different angles, and break up to create negative space.

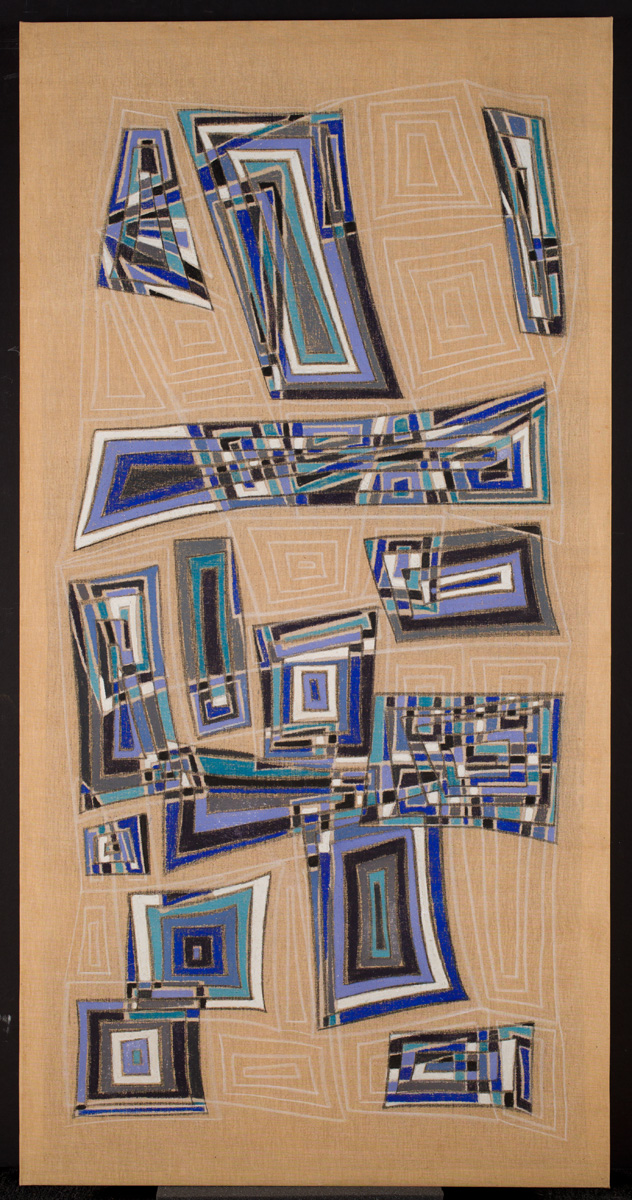

Myra Landau (Bucharest, Romania 1926 – 2018 Alkmaar, The Netherlands), Ritmo de invierno (Winter Rhythm), 1976, Pastel on raw linen, Museum purchase, The Class of 1947 Acquisition Fund 2018.278. Courtesy of the artist's estate.

Myra Landau and her family fled Romania for Brazil during World War II. In 1959, she moved to Mexico, where she joined a group of younger abstractionists who declared their distance from social realism and political art. Beginning in the mid-1960s, she developed her signature style, using pastel on raw linen to create mazelike compositions loosely inspired by contemporaneous movements like kinetic and op art. The color range in this work refers less to winters in Mexico than to internal emotions, reflected as well in Landau’s freely drawn, non-industrial approach.

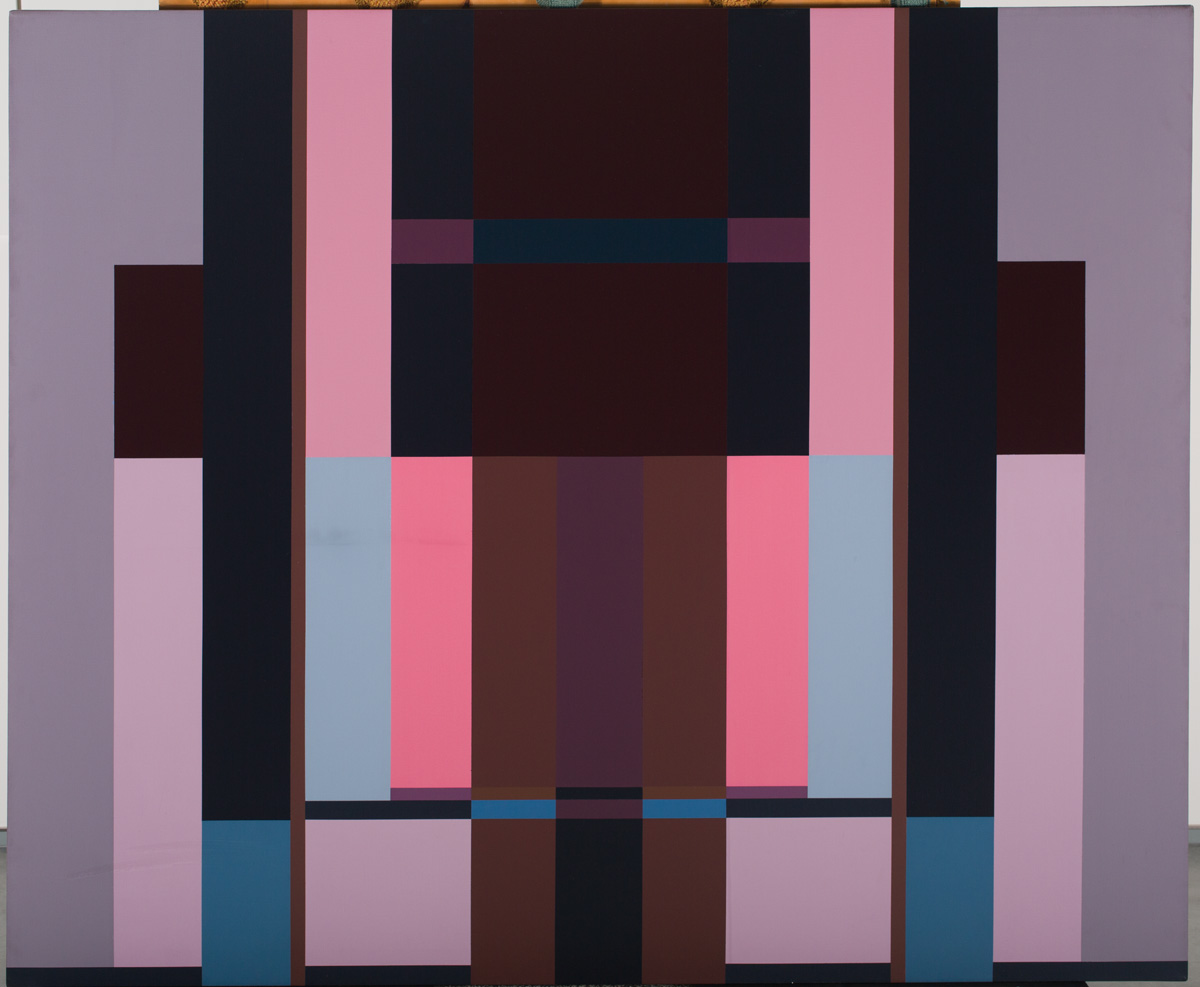

Fanny Sanín (b. 1938 Bogotá, Colombia), Acrylic No. 7, 1978, Acrylic on canvas, Gift of the artist 2017.159. Courtesy of the artist.

Fanny Sanín lived and worked in her native Colombia, then in Mexico and England, before finally settling in the United States in 1971. Sanín’s recognition of the potential of flexible symmetrical structures—and her long-term commitment to this type of composition—has led to complex investigations into the intricacies of color and geometric relationships. Although symmetry implicitly achieves an overall balance, Sanín uses color and shape to create an active and dynamic field that challenges viewers to look closely and slowly.