Luther’s Theology

Lucas van Leyden, St. Jerome, 1513, Engraving, Anonymous gift 1934.25

In 1520, Pope Leo X issued a papal bull (Exsurge Domine) commanding Luther to recant many of his writings. After publicly burning the bull, Luther was officially excommunicated. Declared an outlaw by the emperor (in the Edict of Worms), he went immediately into hiding at Wartburg Castle under the protection of Elector Frederick of Saxony. During this time, Luther’s celebrity grew, and his writings continued to circulate and gain traction. It is likely that this celebrity helped to save him from execution. At Wartburg, he began one of his most lasting projects: a new translation of the Bible into German.

During this time, Luther continued to clarify his theology, concluding that humans could not free their souls from sin through works or intercession. The medieval Church had long emphasized the importance of pious good works and the intercession of saints, even as theologians had debated about the precise nature of the cooperation between the Church, God, and the individual in his or her salvation. For Luther, human beings could be justified (i.e. freed from the burden of their sins) through God’s grace alone (sola gratia), based on their belief in the Savior (sola fide); and not by means of man-made traditions such as the sacraments, but only by God’s holy scripture (sola scriptura). These foundational beliefs eschewed the need for priestly and heavenly intercessors (priests, the Pope, and the saints), redefined some sacraments and rendered others obsolete, and fixed scripture at the center of theological doctrine and religious practice.

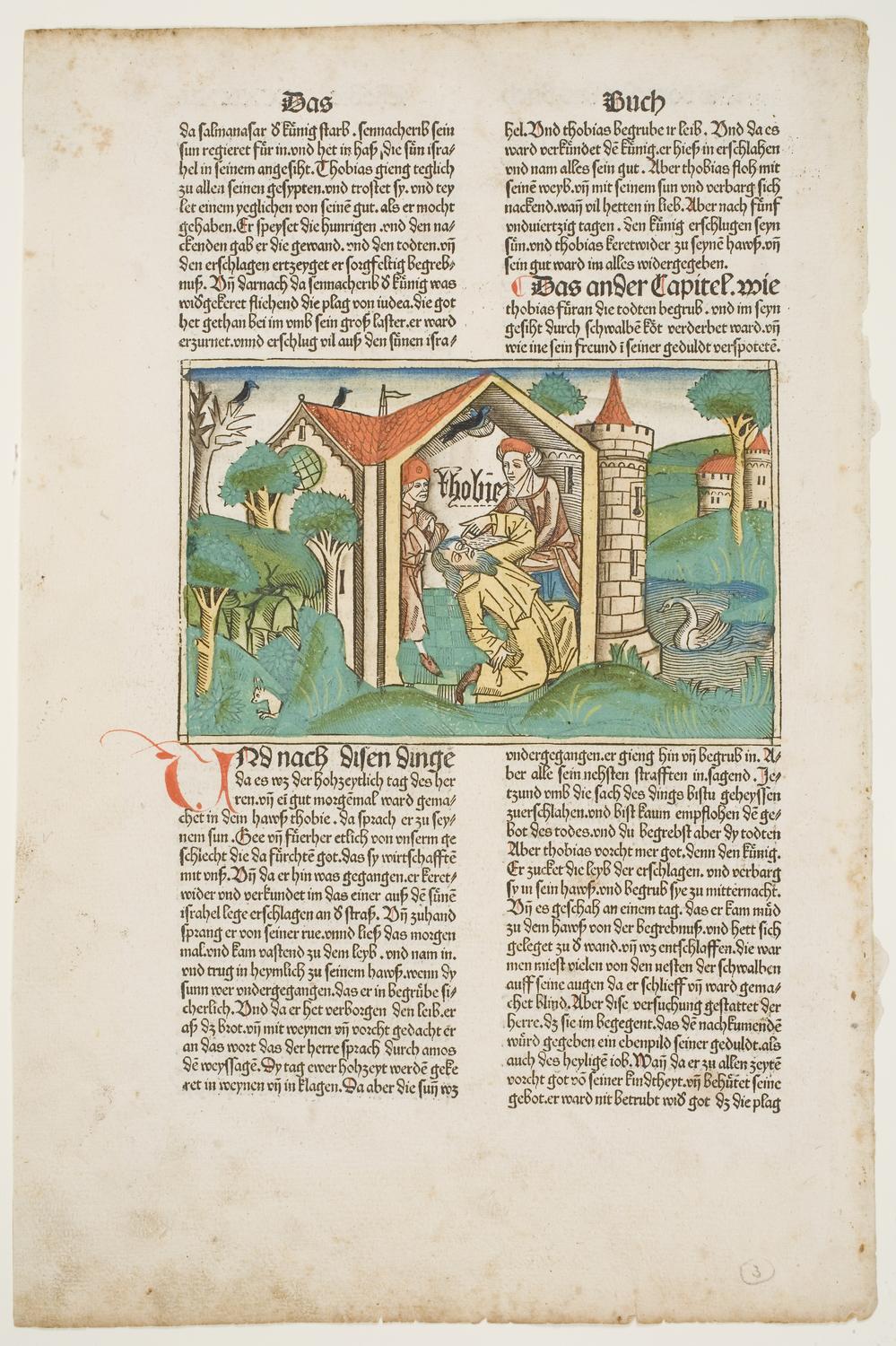

Anton Koberger, The Blinding of Tobit, from Anton Koberger’s German Bible, 1483, Color woodcut, Gift of Mrs. William F. Stearns 1989.34

Before Luther’s translation, there were several German-language bibles produced, starting in the fourth century. The two leaves above come from Anton Koberger, German publisher and godfather of Albrecht Dürer. Koberger’s bible, published in 1483, was translated from the Vulgate into High German and included many woodcuts. Koberger’s press employed close to 100 workers at its height in the late fifteenth century; its greater effort was the monumental Nuremberg Chronicle, a monumental illustrated encyclopedia of world events.

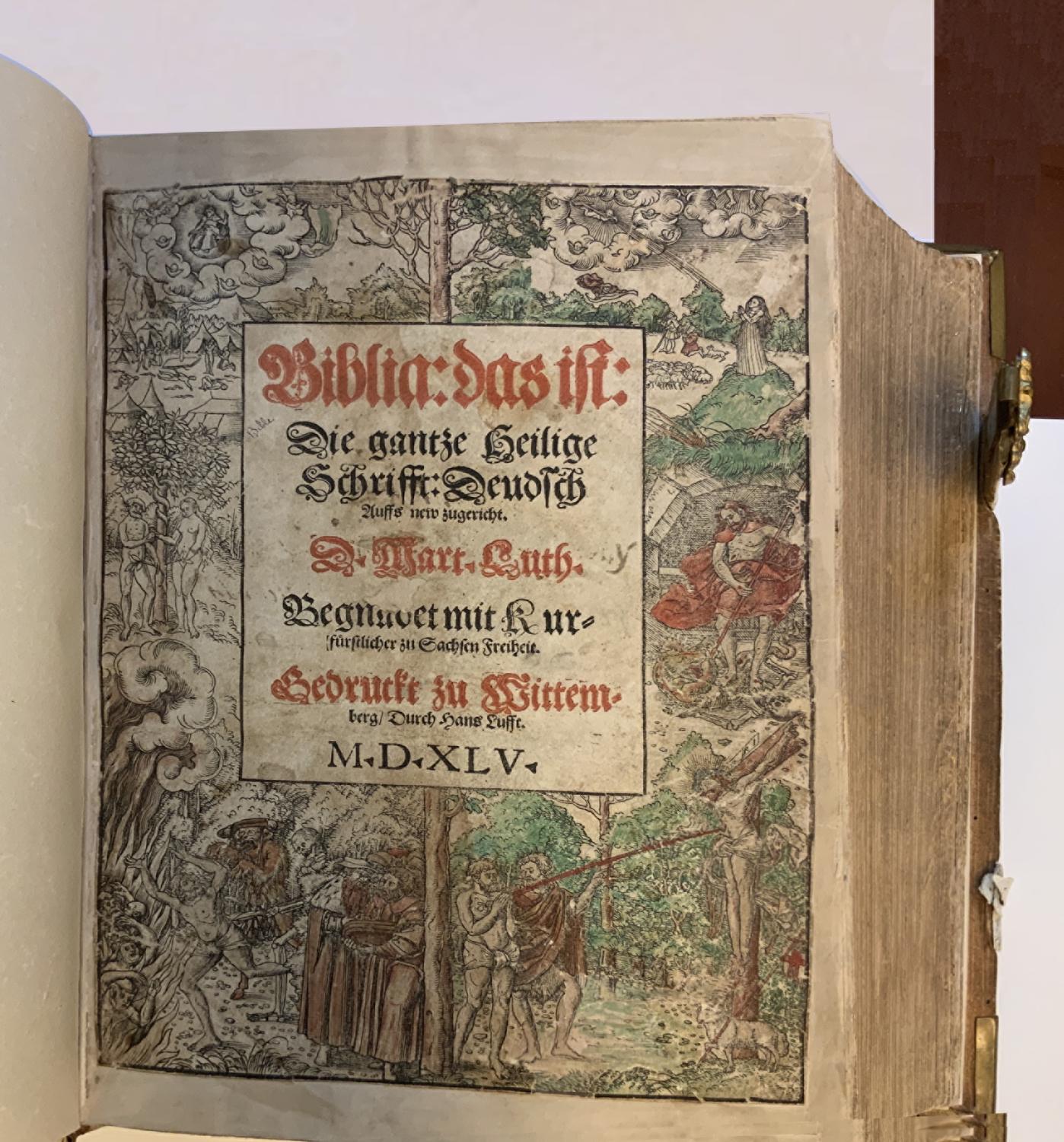

Translated into German by Martin Luther, Illustrations by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Bible, 1545, Printed in Wittenberg by Hans Lufft, Margaret Clapp Library, Wellesley College Special Collections

For his translation of the Bible, Luther returned to Greek and Hebrew sources that predated Jerome’s fourth-century Vulgate Bible. Luther completed the New Testament in 1522, and the Old Testament in 1534. Both were widely circulated and amply reprinted with many woodcuts to reinforce their written message. This Bible includes a title page featuring the so-called Law and Grace iconography, an image created by Lucas Cranach at the behest of Luther, and the only original Lutheran contribution to Christian iconography. In it, the Old Testament scenes on the left illustrate the threat of divine punishment conveyed by the law of God, while the right side depicts the grace of God, given to mankind through the sacrifice of Christ. The iconography was designed to be a striking and memorable instrument for propagating Luther’s concept of justification by faith alone—the most important theological development of the Reformation.

Albrecht Dürer, The Prodigal Son Amidst the Swine, 1496, Engraving, Gift of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlain, Class of 1929) 1968.35

Luther’s emphasis on scripture demanded a close look at the teachings of the Old and New Testaments, creating a focus on biblical stories as examples of faith. Protestant artists paid particular attention to the parables of the New Testament, which were understood as spiritual lessons issued from the authority of Christ himself. The parable of the prodigal son—whose profligate ways are forgiven by his father, who then treats him with the same love afforded to his older, responsible brother—was seen as an example of Luther’s doctrine of justification wherein individuals are forgiven of their sins and made righteous before God by virtue of their faith alone.

Martin Treu, Prodigal Son Amidst the Swine and The Return of the Prodigal Son, ca. 1540, Engraving, Bequest of Ann Kirk Warren (Ann Haggerty, Class of 1950) 2016.468-.469

Albrecht Dürer, Title Page from the Small Passion, ca. 1509, Woodcut, Bequest of Ann Kirk Warren (Ann Haggerty, Class of 1950) 2016.523

Albrecht Dürer, The Last Supper, from the Small Passion, ca. 1508–09, Woodcut, Gift of William F. Stearns 1990.11

The Passion of Christ—the events surrounding his persecution and death—is central to Lutheran theology: it is understood as the sacrifice through which sinners are made righteous, and is at the core of the doctrine of justification. Many sixteenth-century artists—including Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Lucas van Leyden—created print series of Passion events for private devotion, often with additional scenes meant to connect the Passion to the greater history of salvation. For example, Dürer’s so-called Small Passion—printed as a small format book—includes thirty-seven woodcuts of scenes from the Fall to the Last Judgment, accompanied by explanatory texts. In their intimate composition, the images focus on Christ’s suffering through contemplation of his body and the instruments of his Passion. In his Last Supper, Dürer features both the chalice and bread prominently at the center of the table, perhaps as a nod to the utraque specie debate, in which reformers argued for the distribution of bread and wine to all congregants, rather than just priests at the mass. Although this book pre-dates Luther’s reform, it was collected and valued long afterwards.

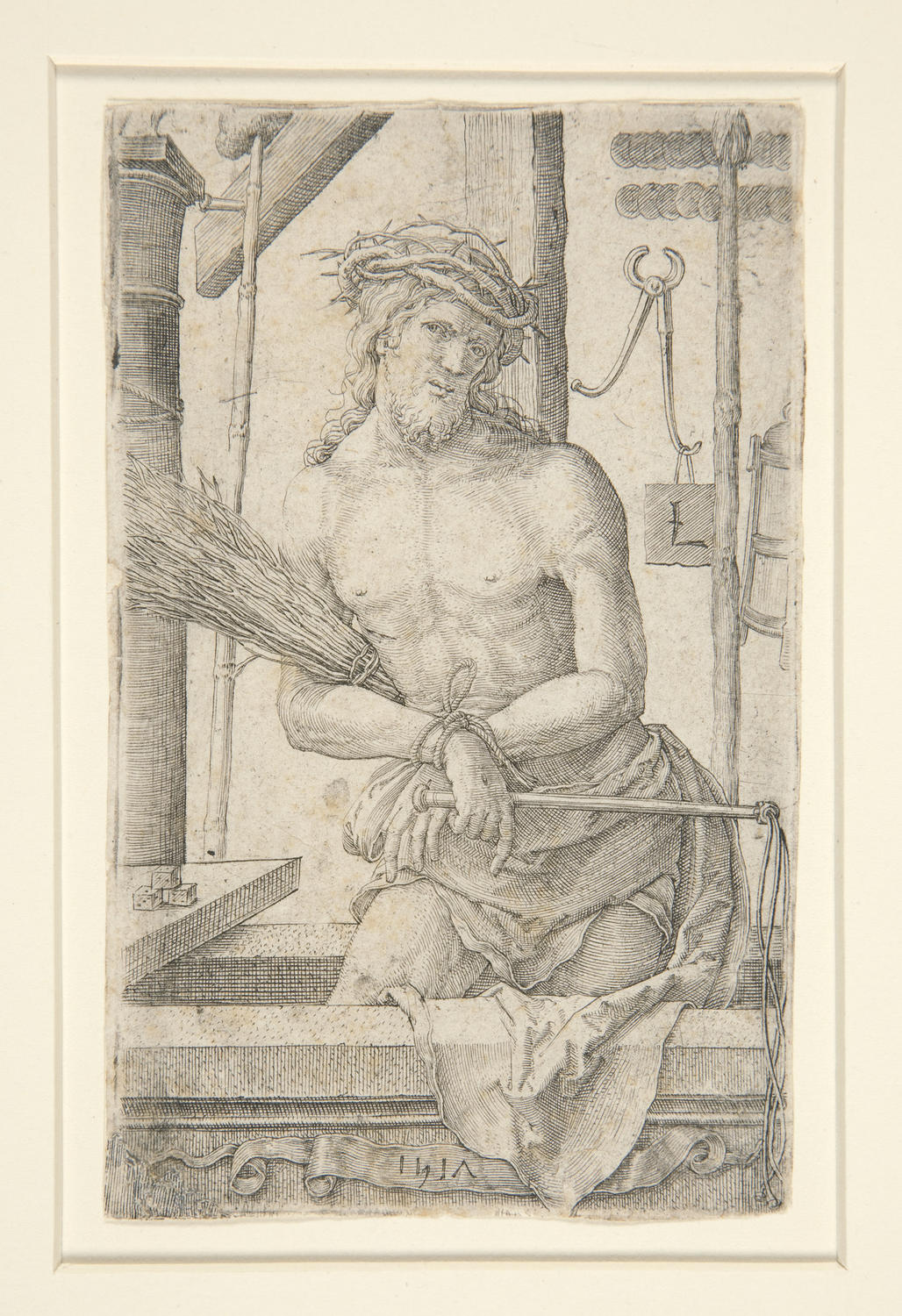

Lucas van Leyden, Christ as the Man of Sorrows with the Instruments of the Passion, 1517, Engraving, Yale University Art Gallery, University Purchase Fund, 1956.9.19

In a sermon published in 1519, Martin Luther argued that a person who contemplates Christ’s sufferings for a day, an hour, or even a quarter hour would do better than to fast for a year or attend a hundred masses. Images from the Passion of Christ served as aids to contemplation by emphasizing his suffering. This image of the Man of Sorrows surrounded by instruments of the Passion was a particularly potent stimulus to prayer. So moved by the isolated and broken body of Christ, the Christian viewer was meant to consider the nature of his sacrifice and its relationship to grace and salvation.

Albrecht Dürer, The Apocalyptic Woman and the Seven-Headed Dragon, ca. 1497, Woodcut, Bequest of Ann Kirk Warren (Ann Haggerty, Class of 1950) 2016.558

In 1498, Dürer published fifteen woodcuts as full-page illustrations to the Book of Revelation. While drawn from an earlier tradition of biblical illumination, Dürer’s woodcuts were unprecedented in their complexity and scale. The scenes follow quite faithfully the vivid visions described by Saint John, and they achieved unqualified success on the market. After the first printing of Martin Luther’s New Testament in 1522, artists attempting to illustrate the text of Revelation relied heavily on Dürer’s model.

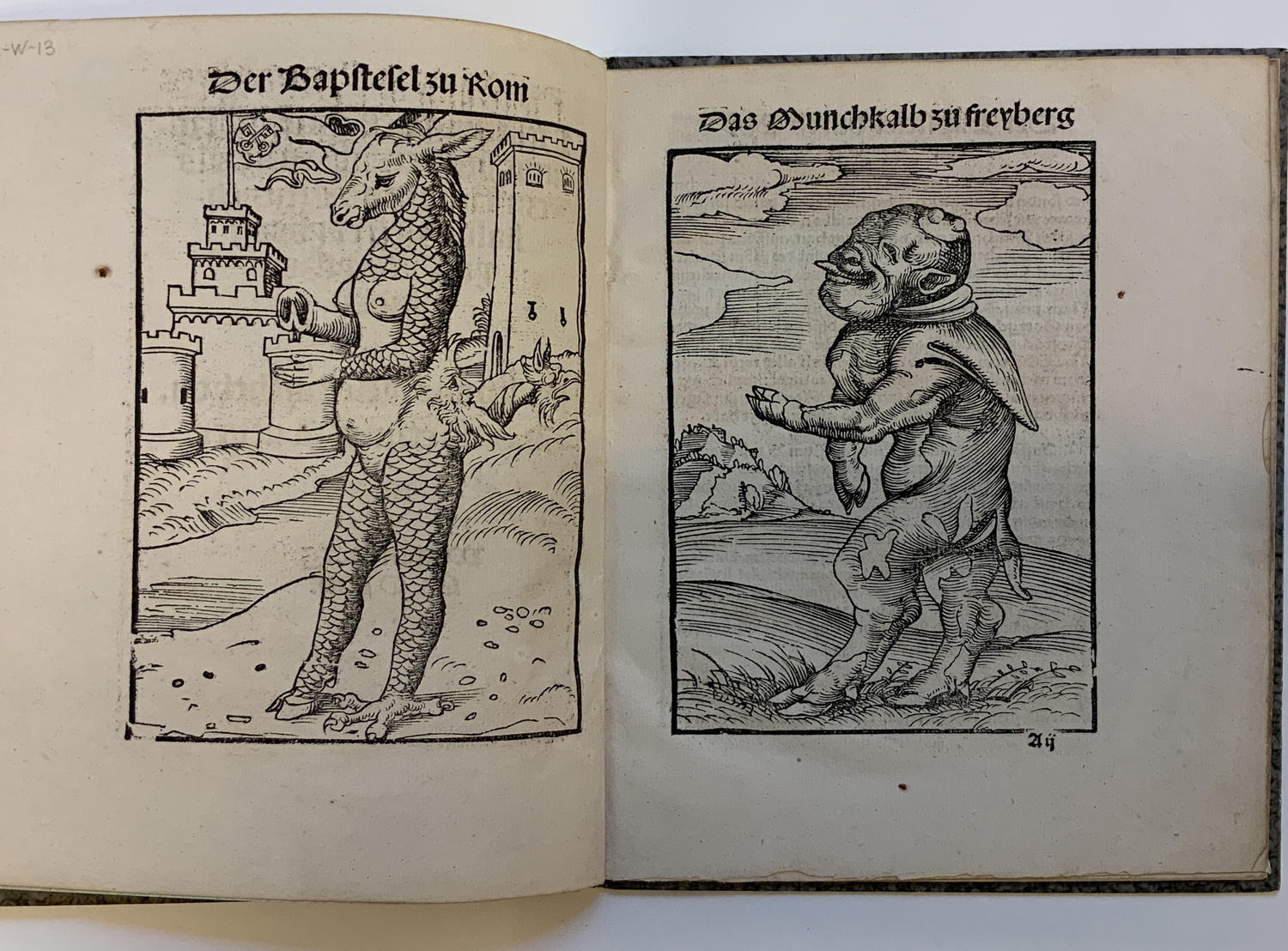

Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, Illustrations by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Dettung der zwo grewlichen Figuren: Bapstesels zu Rom, und Munchkalbs zu Freyberg in Meyssen funden (Interpretation of the Two Dreadful Figures of the Pope Donkey in Rome and the Monk Calf, Found at Freiberg in Meissen), 1523, Printed in Wittenberg by Johann Rhau-Grenenberg, Margaret Clapp Library, Wellesley College Special Collections

Published the year following Martin Luther’s German translation of the New Testament, this pamphlet was a best-selling anti-Papal polemic. Like Luther’s Bible, it is written in vernacular German and includes graphically arresting images created by Lucas Cranach. The pamphlet includes essays on two monstrous births: one, about a donkey with papal attributes found drowned in the Tiber River, and the other about a calf with the tonsure and cowl of a monk born in December of 1522. Stories of deformed animal births—often understood to be signs of the impending Apocalypse—were popular tropes in the late Middle Ages. Here, Melanchthon and Luther interpret the deformities of the animals as allegories for the abuses of the Papacy and the Church, an interpretation that Cranach reinforces by emphasizing the peculiar markings on the calf’s head and the folds of skin around his neck.