Peasants, Fools, and Witches

Hans Sebald Beham, Two Couples and a Fool, 1st half of the 16th century, Engraving, Gift of Mrs. Toivo Laminan (Margaret Chamberlain, Class of 1929) 1962.6.2

From the beginning of the sixteenth century, texts and polemics began to question class hierarchies and the feudal organization that structured society. Luther’s focus on religious equality saw greater application outside of theology: his “priesthood of all believers” was cited as a cause of the Great Peasants’ Revolt in 1524-5. The erosion of the feudal system led to shifts in the status of other members of society as well, particularly the lesser aristocracy. Scholars have debated the reasons for a marked rise in non-religious subjects in art, pairing the diminishing centrality of (and, at times, hostility towards) art in religious practice with an increase in the taste for works that explore topics beyond the lives of Jesus and the saints. Renaissance Humanism played a role as well: in this age of scientific enlightenment and scrutiny of institutions and human behavior, subject matters such as folly, peasants, mortality, and the occult found creative expression in the work of Northern artists.

Heinrich Aldegrever, Wedding Dancers, 1538, Engraving, Museum purchase 1990.43

For all levels of society, pageantry was an important means of projecting status and power. Processions provided the opportunity to display wealth and connections, as Aldegrever does here in this elegant print depicting wedding dancers.

Hans Sebald Beham, The Lady and Death, 1541, Engraving, Gift of Herbert V. Olds 1977.50

Lucas van Leyden, Untitled (Man holding Skull), 1519, Engraving, Bequest of Ann Kirk Warren (Ann Haggarty, Class of 1950) 2016.444

In the late Middle Ages, the image of a skull almost always served as a memento mori—a reminder of the brevity of life and the inevitable fate that all humans must meet.

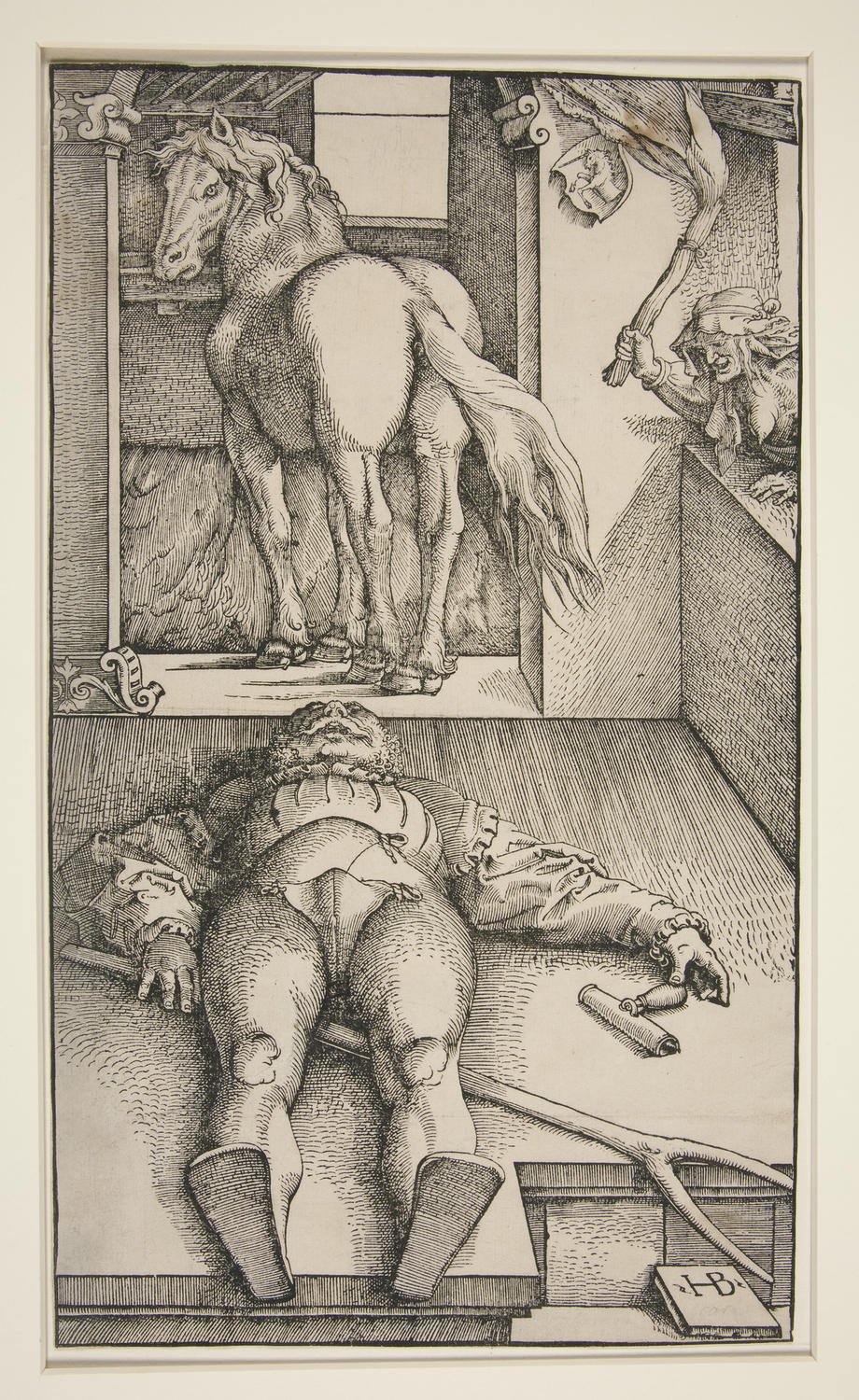

Hans Baldung (called Grien), The Bewitched Groom, 1544–45, Woodcut, Yale University Art Gallery, University Purchase, Maitland F. Griggs, B.A. 1896, Fund, 1951.9.12

Late fifteenth-century Germany saw a rise in stories and superstitions of witchcraft, a trend that mirrors the destabilization of social hierarchies at the time. The Swabian artist Hans Baldung, a student in Dürer’s workshop in the early 1500s, specialized in scenes of witchcraft; his artistic compositions were both highly popular and without artistic precedent. In The Bewitched Groom, Baldung illustrates an enigmatic scene, perhaps a popular story of a robber stalked by the devil and killed by a kick from a fiendish mount. The bare-breasted woman waving a torch through the window, as well as the forked staff and agitated horse, were all understood to be mysterious and nefarious actors in the supernatural world.