Adjusting to life in the U.S. and at college can be challenging, no matter how much time you have spent abroad or in the U.S. International students often experience culture shock, which is common, but it is good to understand how and why it happens, as well as where to turn if you are experiencing feelings of homesickness.

Culture Shock

Stages of Culture Shock

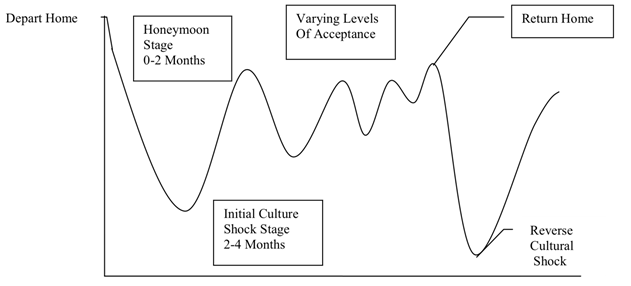

The discomfort experienced while adjusting to life in a culture different from one‘s own is often called culture shock.

Symptoms

Strain: due to having to make so very many psychological adaptations without any sort of respite

Sense of loss and feelings of deprivation: regarding the status, friends, possessions, etc. to which you were accustomed and feel you are due, but no longer have

Rejection: feeling that you are rejected by members of the new culture and/or you are rejecting members of the new culture

Confusion: in roles, expectations, values, feelings, and self-identity

Surprise, anxiety, and indignation: after becoming aware of the many cultural differences that exist between your home and the host cultures

Feelings of inadequacy: due to fear of not being able to succeed in the new culture

Art of Sympathy

The practice of empathy can be seen as a three-stage process:

- Recognize that the other person does, in fact, have a different point of view. He or she is looking at the situation through his or her own unique filter of experiences, biases, and values. This is the easiest part of the empathy process because it is so obvious and because it is a rational, logical and intellectual step.

- Accept the idea that it is all right for another person and this one in particular, to have a viewpoint that is different from yours. Most people find this much more difficult stage of the empathy process. Often when we find that another person has a different viewpoint, our impulse is to ‘get it shaped up.' ( Note that this second step doesn't mean adopting, or even approving of, the specific opinion another person has, only accepting the idea that it is all right for that person to be unique and have a different set of experiences from those you have. )

- The final step in the practice of empathy might be expressed. "I really want to understand your point of view―not judge it, shape it up, argue with it. or endorse it ; I just want to understand.” If that is your attitude, the way that you are feeling about the relationship and the discussion, then it will not be necessary to verbalize that attitude. It will be apparent in your behavior.

Adapted from L. Robert Kohls

Values Americans Live By

Dr. L. Robert Kohls, Director of International Programs at San Francisco State University, is a renowned literary contributor to the research on cultural patterns. He has developed a list of 13 commonly held values, which help explain to first-time visitors to the United States why U.S. Americans act as they do. He is careful to avoid labeling these values positive or negative. Whether you agree with Kohls or not, his observations are thought provoking.

Personal Control over the Environment

U.S. Americans do not believe in fate, and they tend to look at people who do as being backward, primitive, or "native." In the U.S. American context, to be "fatalistic" is to be superstitious, lazy, or unwilling to take initiative. Everyone should have control over whatever in the environment might potentially affect him or her. U.S. Americans attribute problems as coming from laziness or unwillingness to take responsibility in pursuing a better life, rather than due to simple bad luck or "fate."

Change Seen as Natural and Positive

In the U.S. American mind, change is seen as indisputably good, leading to development, improvement, and progress. Many older, more traditional cultures consider change disruptive and destructive; instead they value stability, continuity, tradition, and a rich and ancient heritage, none of which are considered very important in the United States.

Time and Its Control

Time is of utmost importance to most U.S. Americans. It is something to be on, kept, filled, saved, used, spent, wasted, lost, gained, planned, given, even killed. U.S. Americans are more concerned with getting things accomplished on time than they are with developing interpersonal relations. Their lives seem controlled by the little machines they wear on their wrists, cutting their discussions off abruptly to make their next appointment on time. This philosophy has enabled U.S. Americans to be extremely productive, and productivity is highly valued in their country.

Equality and Fairness

Equality is so cherished in the United States that it is seen as having a religious basis. U.S. Americans believe that all people are "created equal" and that all should have an equal opportunity to succeed. This concept of equality is strange to seven-eighths of the world that view status and authority as desirable, even if they happen to be near the bottom of the social order. Since U.S. Americans like to treat foreigners "just like anybody else," newcomers to the U.S. should realize that no insult or personal indignity is intended if they are treated in a less-than-deferential manner by waiters in restaurants, clerks in stores and hotels, taxi drivers, and other service personnel.

Individualism and Independence

U.S. Americans view themselves as highly individualistic in their thoughts and actions. They resist being thought of as representatives of any homogeneous group. When they do join groups, they believe they are special, just a little different from other members of the same group. In the U.S., you will find people freely expressing a variety of opinions anywhere and anytime. Yet, in spite of this "independence," almost all U.S. Americans end up voting for one of their two major political parties. Individualism leads to privacy, which U.S. Americans see as desirable. The word "privacy" does not exist in many non-Western languages. If it does, it is likely to have a negative connotation, suggesting loneliness or forced isolation. It is not uncommon for U.S. Americans to say, and even to believe: "If I don't have half an hour a day to myself, I go stark-raving mad!"

Self-Help/Initiative

U.S. Americans take credit only for what they accomplish as individuals. They get no credit for having been born into a rich family but pride themselves in having climbed the ladder of success, to whatever level, all by themselves. The equivalent of these words cannot be found in most other languages. It's an indicator of how highly U.S. Americans regard the "self-made" man or woman.

Competition

U.S. Americans believe that competition brings out the best in any individual in any system. Value is reflected in the economic system of "free enterprise" and it is applied in the U.S. in all areas ‐ medicine, the arts, education, and sports.

Future Orientation

U.S. Americans value the future and the improvements the future will surely bring. They devalue the past and are, to a large extent, unconscious of the present. Even a happy present goes largely unnoticed because U.S. Americans are hopeful that the future will bring even greater happiness. Since U.S. Americans believe that humans, not fate, can and should control the environment, they are good at planning short-term projects. This ability has caused U.S. Americans to be invited to all corners of the Earth to plan, and often achieve, the miracles, which their goal-setting methods can produce.

Action/Work Orientation

"Don't just stand there," says a typical bit of U.S. American advice, "do something!" This expression, though normally used in a crisis situation, in a sense describes most U.S. Americans' waking life, where action - any action - is seen as superior to inaction. U.S. Americans routinely schedule an extremely active day. Any relaxation must be limited in time and aimed at "recreating" so that they can work harder once their "recreation" is over. Such a "no-nonsense" attitude toward life has created a class of people known as "workaholics" ‐ people addicted to, and often wholly identified with, their profession. The first question people often ask when they meet each other in the U.S. is related to work: "What do you do?" "Where do you work?" or "Who (what company) are you with?" The United States may be one of the few countries in the world where people speak about the "dignity of human labor,‘ meaning hard physical labor. Even corporation presidents will engage in physical labor from time to time and, in doing so, gain rather than lose respect from others.

Informality

U.S. Americans are even more informal and casual than their close relatives, the Western Europeans. For example, U.S. American bosses often urge their employees to call them by their first names and feel uncomfortable with the title "Mr." or "Mrs." Dress is another area where U.S. American informality is most noticeable, perhaps even shocking. For example, one can go to a symphony performance in any large U.S. American city and find people dressed in blue jeans. Informality is also apparent in U.S. Americans greetings. The more formal "How are you?" has largely been replaced with an informal "Hi!" This greeting is likely used with one's superior or with one's best friend.

Directness/Openness/Honesty

Many countries have developed subtle, sometimes highly ritualistic ways of informing others of unpleasant information. U.S. Americans prefer the direct approach. They are likely to be completely honest in delivering their negative evaluations, and to consider anything other than the most direct and open approach to be "dishonest" and "insincere." Anyone in the U.S. who uses an intermediary to deliver the message will also be considered "manipulative" and "untrustworthy." If you come from a country where saving face is important, be assured that U.S. Americans are not trying to make you lose face with their directness.

Practicality/Efficiency

U.S. Americans have a reputation for being realistic, practical, and efficient. The practical consideration is likely to be given highest priority in making important decisions. U.S. Americans pride themselves in not being very philosophically or theoretically oriented. If U.S. Americans would even admit to having a philosophy, it would probably be that of pragmatism. Will it make money? What is the "bottom line?" What can I gain from this activity? These are the kinds of questions U.S. Americans are likely to ask, rather than: Is it aesthetically pleasing? Will it be enjoyable? Will it advance the cause of knowledge? This pragmatic orientation has caused U.S. Americans to contribute more inventions to the world than any other country in human history. The love of "practicality" has also caused U.S. Americans to view some professions more favorably than others. Management and economics are much more popular in the United States than philosophy or anthropology, and law and medicine more valued than the arts. U.S. Americans belittle "emotional" and "subjective" evaluations in favor of "rational" and "objective" assessments. U.S. Americans try to avoid being "too sentimental" in making their decisions. They judge every situation "on its own merits."

Materialism/Acquisitiveness

Foreigners consider U.S. Americans more materialistic than they are likely to consider themselves. U.S. Americans would like to think that their material objects are just the "natural benefits" that result from hard work and serious intent - a reward, which all people could enjoy were they as industrious and hard working as U.S. Americans. But by any standard, U.S. Americans are materialistic. They give a higher priority to obtaining, maintaining, and protecting material objects than they do in developing and enjoying relationships with other people. Since U.S. Americans value newness and innovation, they sell or throw away possessions frequently and replace them with newer ones. A car may be kept for only two or three years, a house for five or six before buying a new one.