A Boxing Fan Campaigns to Elect Wellesley Alumna as First Woman in the International Boxing Hall of Fame

In 1938, American boxing legend Joe Louis fought Max Schmeling in a rematch for the world heavyweight boxing championship in Yankee Stadium. Schmeling was white and from Germany; Louis was black and American. Schmeling had defeated Louis in an earlier fight.

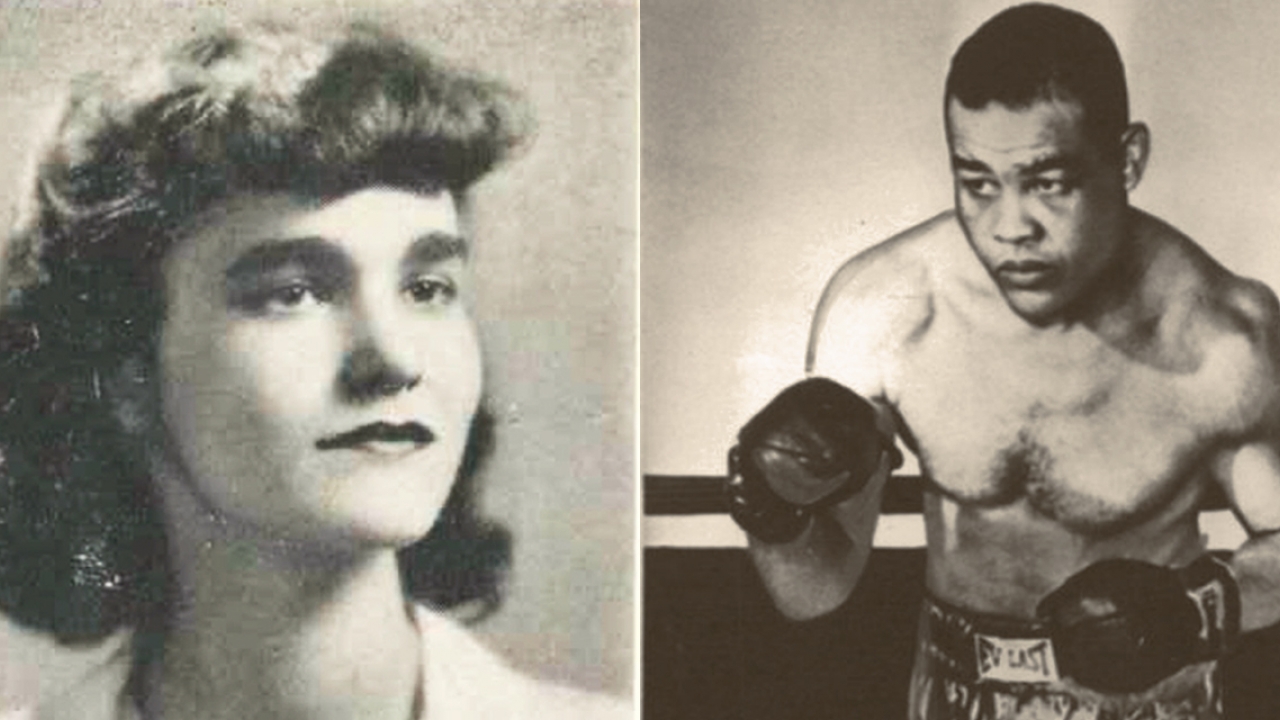

In the audience that night was Margery Miller ’45, then a 15-year-old from Springfield, Vt. Her father had bought tickets so that they could both watch the biggest fight of its time, a battle rife with social, racial, and political overtones.

Louis knocked out Schmeling. The punch heard around the world won Louis a dedicated fan in Miller. She had followed boxing from an early age, listening with her father to bouts on the radio and poring over stories by legendary boxing writer Nat Fleischer, and that night she found her calling.

At Wellesley, Miller majored in English composition and received the Florence Annette Wing Memorial Prize for Lyric Poetry. She loved writing and literature. She also still loved boxing. Miller wrote her senior thesis about Joe Louis, and the year she graduated it became a published book: Joe Louis: American.

In Louis, Miller saw something deeper than his performance in the boxing ring, said Roy Peter Clark, vice president and senior scholar at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Clark, both a journalist and boxing buff, came across Miller’s book at a sale in Florida more than a decade ago. Her story, printed on the book jacket along with her picture, sparked his curiosity, so he travelled to Wellesley and read through archival files on Miller to get a full sense of her background. His research informed his opinion, explained in a piece in The Undefeated, a platform that explores the intersections of race, sports, and culture, that Miller deserves to be the first woman inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Miller, he learned, was a trailblazer, covering a hard-boiled sport that was the domain of men. She saw in Louis a symbol of self-respect for African Americans and a trailblazer in his own right, he said.

“Here was this young woman from Vermont, a Wellesley student, in the sweaty, brutal world of boxing,” Clark said in an interview. “She never flinched.”

Miller wrote in her book of the Louis-Schmeling fight:

“Schmeling went down three times. When he got up the third time, his legs were sand and his hands hung useless at his sides. He looked like a grotesque drunk who could neither think nor act… ‘Oh, Joe! Oh, Joe! Oh, Joe!’ The crowd now came near to having only one voice. It howled and shrieked. It stood on its chairs and tore its hats to bits. It jumped up and down in its frenzy. ‘Oh, Joe. Oh, Joe.’ It drowned out the formal announcement of Louis’ victory. Seventy thousand people had gone insane.”

After graduating from Wellesley, Miller covered sports for New York-based Kings Features Syndicate from 1945 to 1947. From 1951 to 1953, she edited trade books for E.S. Barnes & Co.

Eventually, she got back to boxing. Sports Illustrated hired her as one of its first writers in 1953. She also wrote about boxing in a weekly column for the Christian Science Monitor from 1946 to 1961.

Miller died in 1985, in Charlotte, N.C.

Clark wants the International Boxing Hall of Fame to induct Miller under the category called “Observers.” He has started a personal campaign to elevate her name in the boxing world.