Wellesley Professor Explains the Rise of Reggaeton in North American Pop

You can count on one hand the number of primarily Spanish-language songs that have reached number one on the U.S. pop charts over the last three decades. Los Lobos took its cover of “La Bamba” to the top of Billboard Hot 100 exactly 30 years ago, the first Spanish-language single to reach the number-one slot. In 1996, Los Del Rio’s “Macarena” became the second. And in May of this year, Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee, and Justin Bieber reached the number-one slot with “Despacito”—a song that, like “Macarena,” makes everyone want to dance.

When writer Spencer Kornhaber was looking for some context about this history-making hit for an article in The Atlantic, he spoke with Petra Rivera-Rideau, assistant professor of American studies at Wellesley and author of Remixing Reggaeton: The Cultural Politics of Race in Puerto Rico. In a Q&A with Kornhaber, she described the complex lineage of the song and the effects of Justin Bieber popularizing it in the United States. Bieber is Canadian; the Canadian Broadcasting Company also interviewed Rivera-Rideau to get some perspective on the song’s trajectory.

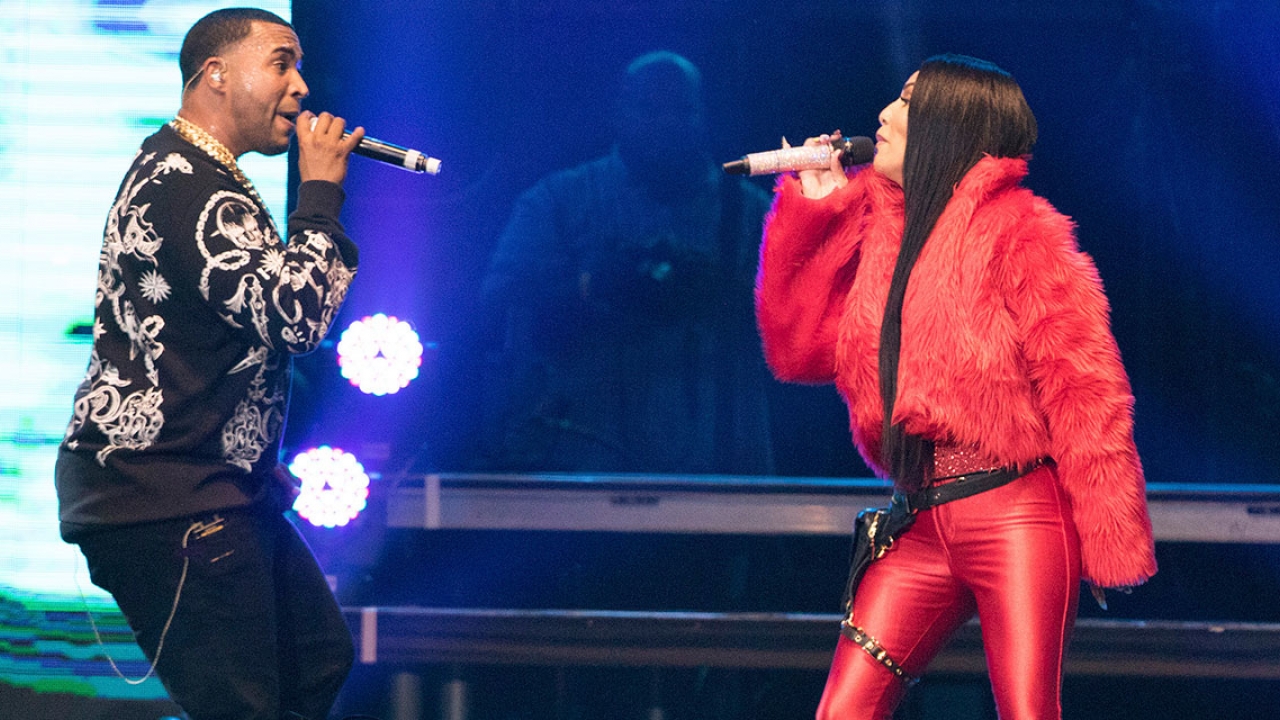

Even before “Despacito” got a boost from Bieber, it was soaring on Latin charts and lighting up dance floors with its cuatro Spanish guitar intro and the reggaeton beat that drives the rhythm. “It’s not like Justin Bieber came on a kind of unknown song,” Rivera-Rideau told the CBC. “This was a really, really popular song. Also, there’s a general turn in popular music, a kind of Caribbean sound, and ‘Despacito’ rides that wave. So it seemed sort of like a perfect formula for getting into the Hot 100.”

It wasn’t Luis Fonsi or Daddy Yankee who’d envisioned a Hot 100 hit with the Bieber remix, Rivera-Rideau explained; rather, Bieber contacted them after hearing the song in Colombia while he was on tour. “So I think that this helps complicate some of these narratives about how Latin music artists always aim to sing in English and cross over to the English market,” she added.

Bieber already knew something about reggaeton. A remix of his 2016 hit “Sorry” featured the Colombian reggaeton sensation J Balvin.

Rhythm is one of the key characteristics of the genre, according to Rivera-Rideau. She told the CBC, “For me it’s really the beat. One element that does go through many reggaeton songs is [that] beat—like ‘boom cha-boom chick, boom cha-boom chick.’ And when you get to the buildup of the chorus, it’s very prominent.”

Rivera-Rideau’s book is partly about the racial dynamics in reggaeton. “We wouldn’t have reggaeton if we didn’t have complicated historical patterns of migration in the Caribbean basin,” she said in her conversation with Kornhaber. “A very basic idea of what ingredients produced reggaeton would be hip-hop coming from the U.S., dancehall based out of Jamaica, and a type of music called Reggae en Español from Panama in particular.”

But, she added, the origin of reggaeton is contested. “Did Puerto Ricans make reggaeton or did Panamanians make reggaeton? One of the things that brings all of these things together is that many of these musics come from urban, predominantly black, working-class communities—whether they’re from Kingston or Panama City or New York or San Juan.”

In her book, she specifically addresses the Puerto Rican context. “In Puerto Rico,” she told Kornhaber, “there’s a sense that the island’s trinity of races—black, Spanish, and indigenous—has produced a harmonious society with no racism. But when you look at things like who has access to education, or at housing segregation, it’s very clear Afro-Puerto Ricans are discriminated against. Reggaeton provided a space to talk about those issues.”

Artists such as Ivy Queen and Don Omar figure prominently in Rivera-Rideau’s book, as using reggaeton to articulate connections between Puerto Ricans and other Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino populations, a history that she said gets obscured through the emphasis on “Despacito” as a crossover Latino phenomenon. She said, “This history also shows that, while there’s much discussion about Justin Bieber adopting reggaeton, there were already complex racial dynamics at play with the Luis Fonsi version before the re-mix that should not be ignored.”

Rivera-Rideau said, what led her to this project was her long-standing interest in racial justice and popular music – an interest that developed in part because of her father’s influence. She said her father had done a great deal of community organizing and social justice work with Puerto Rican communities in Ohio and Connecticut, and also has a sizable music collection, especially salsa. So, she said, he instilled in her both this love of music and desire to work on social justice issues.