/ Muslims Make America Great

Subscribe

/ Muslims Make America Great

Subscribe

The first wave of Muslim Americans arrived on slave ships. They fasted for Ramadan as they cultivated our land, laboring for hours without food and water to provide others with sustenance. Ben Ali Muhammad, a slave in Georgia, was an Imam, leading the other Muslim slaves at his plantation in prayer. His manuscript on Islamic teachings, the Bilali Document, survives to this day at the University of Georgia. In Maryland, Ayuba Suleiman Diallo offered his five daily prayers in the woods, while a white child pelted him with dirt. A lawyer freed Diallo from this distress, taking him to England to meet with Queen Victoria. Another slave, Omar ibn Said, imprisoned after running away, inscribed his jail cell with Arabic words. His cell became something of a tourist attraction, as townspeople clamored to see his coal-based calligraphy. While there is no record of how many slaves were Muslim, scholars estimate that 15 to 30 percent of American slaves adhered to the Islamic faith.

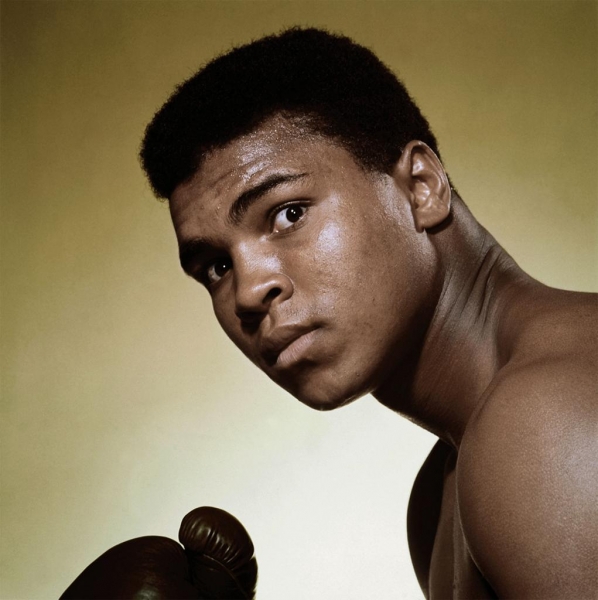

Although many Muslim slaves were forced to convert to Christianity, some managed to preserve their religion. Muslims fought in both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. In 1867, The Nation described Nicholas Said, an African soldier who had served in the Union Army, as capable of being Vice President. Much of this rich American-Islamic history is unknown, both to those who fear Muslims, and to Muslims themselves – Muslims like me. As a former CNN employee, I helped covered then-candidate Trump’s proposed Muslim ban, his musings over ID cards and registries. I helped produce panels where people debated the dangers of people like me. It was hard at times not to feel worthless. I avoided discussing my Islamic heritage until my boss one day shared his love for Muhammad Ali, roping me into watching YouTube videos of the rope-a-dope. So much media coverage centered on Muslim villains, that I had forgotten there could be Muslim heroes – some who could even leave veteran TV producers starstruck. When Ali passed away a few months later, CNN broadcasted the full memorial service in celebration of his life. Despite anticipating the tribute, I was startled by hearing the Islamic call to prayer. After all, one only ever heard “Allah-hu-Akbar” on the news in relation to acts of terror. But this time, millions of Americans heard my prayer just as I had heard it growing up: in the promotion of peace, love, and unity. My mom later recounted line-by-line the eulogies honoring Ali, even though I had heard them all already. I didn’t interrupt her, because I understood how good it felt to be accepted.

“Allah-hu-Akbar” was mentioned again on the news that Sunday, when Omar Mateen murdered 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando. It was the deadliest mass shooting in American history. Mixed with my horror and anguish was shame. Throughout a sleepless night, I wondered how I’d face my gay friends and colleagues the next day. My coworkers and I numbly gathered our strength to produce yet another tribute to victims of terror. Anderson Cooper broke down on air as he read the names of those whose lives had been snatched far too cruelly and far too soon. I cried alongside him, wondering whether I should apologize.

I don’t know if white people felt guilt, like I did that Sunday, when a shooter in Vancouver killed congregants at a mosque, whether they felt the same pangs of anxiety when a man in Kansas murdered two Indian men for appearing Middle Eastern. Neither incident garnered much media coverage or political attention. Despite misplaced remarks on Sweden and France, President Trump has remained silent on these killings. It’s as though terrorist attacks are only terrifying when the perpetrators are Muslim and the victims aren’t. That double standard was apparent last August, when two Trump supporters assaulted a Mexican man in Boston. Then-candidate Trump remarked, “I will say that people who are following me are very passionate. They love this country and they want this country to be great again.” My President saw violent criminals as patriots, but lumped in Muslims like me with the enemy.

I’m now in law school, and I hope to work in the public interest. My time in Sunday School taught me that true success lies only in helping others. But I fear that the public I hope to serve won’t trust me because I’m Muslim. How could I not, after Barack Obama had to deny “accusations” of being Muslim in order to become President? How could I not, after congressmen charged the most visible Muslim woman in politics, Huma Abedin, with disloyalty to her country? How could I not, after the Trump administration won’t even definitively state that Islam is a religion?

But last Sunday, Mahershala Ali became the first Muslim actor to win an Academy Award, for his portrayal of a parental figure to a young gay boy in Moonlight. The White Helmets also won Best Documentary Short for highlighting the heroic work of Muslim volunteer rescue workers in Syria. The producers read a beautiful verse from the Quran: that to save one person is to save all of humanity. The Quran’s insistence on doing what you can had inspired me to apply to law school in the first place. So even as Muhammad Ali, Jr. was detained for having a “Muslim name” – the name of an American icon – even as the Muslim cinematographer for The White Helmets was detained on his way to attend the Oscar ceremony, I know I’ll keep working, in the spirit of the Muslims who came before me. And I have hope that little by little, other Americans too will come to realize that Muslims help make America great.

Sarah Mahmood is a 2014 Albright Fellow who is currently studying at Stanford Law School.

Photo Credit: Philippe Halsman, “Cassius CLAY (Muhammad ALI), American Boxer,” via ARTstor, 1963.