/ Out with the Old, In with the Old

Subscribe

/ Out with the Old, In with the Old

Subscribe

In France’s runoff presidential election, voters will choose between Emmanuel Macron, leader of a newly formed political party, and Marine Le Pen, the leader of the extremist Front National party. François Fillon, the candidate of the mainstream right wing party Les Républicains, came in third, followed by the left wing candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon heading the grassroots movement France Insoumise (Untamed France), while Benoît Hamon, candidate of the Socialist Party, the left-of-center formation currently in power, came in a shockingly distant fifth. France’s 2017 elections are notable for their firsts: for the first time since the founding of the Fifth Republic in 1958, the runoff election will not involve a candidate from either of the two major government parties, Les Républicains or the Socialist Party. Additionally, France’s next president could be its youngest ever, and the first to have never held elected office; or France could have its first female president, and the first to lead an extreme right-wing party to its highest office democratically.

Macron and Le Pen each claim to be political outsiders. But, in fact, in spite of all these superficial novelties, little about either candidate is truly new. France has been here before, in obvious and terrifying ways: a Le Pen—Jean-Marie, Marine’s father, the founder of the Front National—made the runoff elections in 2002 before getting trounced by conservative Jacques Chirac, who was backed by a broad, left-to-mainstream-right democratic front united in its opposition to Le Pen’s crypto-fascist party. There was, however, little left of that original shock on Sunday: Le Pen was expected to reach the second round, an omen read in the ashes of outgoing Socialist president François Hollande’s disastrous term. She did so in trademark style, by painting over the traditional xenophobia of her party and the pro-business protectionism of her economic policies with social rhetoric and vocabulary pilfered from the traditional left wing’s playbook. She notably evokes the separation of church and state or the working class, using buzzwords irrelevant to her actual policies but that helped move her party into a rhetorical territory left virtually vacant by the collapse of the Communist Party and the Socialist Party’s drift towards the interests of big business. She claims that she is running “in the name of the people”: for Le Pen, French citizenship should come by right of blood, a policy that would reverse two hundred years of birthright citizenship.

Though he was virtually unknown to the greater public when he was picked to become Hollande’s Minister of the Economy, Emmanuel Macron has spent much of his career in the halls of power. He has been roundly mocked for his uncanny ability to flip flop on any and all topics. The tenor of his program remained a secret until about two months ago, when he finally released a list of projects in line with the neoliberal policies defended by Hollande. A broad collection of weathered politicians from both sides of the aisle have voiced their support for him. So much for either candidate’s anti-establishment bona fides: a more significant and worrisome sign of a changing era may be that their successes testify to the normalization of the Front National’s extremist rhetoric.

French politics in turn have shifted to place Le Pen at their center; the French speak of a “Lepenization of the minds.” Media fascination for the Front National is only part of the equation: for the past thirty years, the mainstream right and even the government left from Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy to most recently Socialist prime minister Manuel Valls, have channeled the Front National’s xenophobic stance. In the past thirty years, the tendency to portray France’s significant population of North African descent as the country’s foremost problem has steadily grown, compounded by the rise of Islamist terrorism. That the deadliest attacks in France under Hollande were performed by French-born terrorists only exacerbated racial and cultural hostility already cultivated in such befuddling controversies as France’s ban on the Muslim veil. Under Sarkozy, Hollande’s predecessor, the government attempted to foster a nationwide conversation over the meaning of French national identity in the 21st century. The results were dire, and many French politicians revealed an understanding of Frenchness virtually indistinguishable from that of the Front National.

Political beliefs about French identity have been symptoms of the profound impact of the Front National as well as fodder for its growth. Politicians’ positions on matters of French cultural identity have tended to fluctuate widely according to their ideological allegiances and background. This variety makes for heated and titillating debates, but it also bolsters pretenses of fundamental disagreements between parties that often do not exist in economic matters: indeed, in this regard there has been precious little to differentiate the mainstream left from the mainstream right in their successive turns in power. Case in point: the Valls government designed the El Khomri law, a reform of the French labor code for the exclusive benefit of businesses. Among the law’s most loyal backers was Valls’s Minister of the Economy, Emmanuel Macron. Protests backed by most of the trade unions arose throughout the country. In Paris, these developed into Nuit Debout, an occupation movement not unlike Occupy Wall Street and channeled convincingly in Mélenchon’s candidacy, who fell about 2 points short of Le Pen’s score. These protests met with disproportionate force from the authorities, whose increasingly violent actions were systematically defended by Valls. Simultaneously, the prime minister resorted to the much-reviled Article 49.3 of the Constitution to force the unpopular law through Parliament without a vote. Shortly before the law was finally passed, Macron resigned from his position in Valls’s government and announced his bid for the presidency.

Manuel Valls’s career mirrors that of conservative Nicolas Sarkozy in crucial regards: both made a name for themselves as Ministers of the Interior keen on using tough-on-crime language infused with the racial rhetoric typical of the Front National. Chirac before them followed a similar strategy, perhaps inspired by English Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s own successful effort at stealing the British National Front’s nationalist thunder in the late 1970s. Yet French experience has proven that emulating the Front National’s rhetoric has not merely pushed French politics to the right and jeopardized French democracy: it has normalized Le Pen’s party instead of making it irrelevant. Emmanuel Macron’s success this past weekend marks not so much a sea change as the logical latest step in the evolution of French national politics: French people rejected the traditional government parties for the Front National and Macron, a charming young cipher who struggles to distract from the fact that his politics is little more than a synthesis of the two parties he beat. A synthesis with a vengeance: the charade of Macron’s freshness, hammered throughout the campaign in France’s media, is also evidence of his ties to the business elite. A handful of millionaires control France’s major news outlets, which have all voiced their support for one of their own, interview after interview. Macron embodies a political class that privileges the interests of businesses over those of people.

The time his election buys France’s professional politicians is running out: an increasing number of militants, political figures and celebrities on both sides of the aisle have declared that they would sit out the second round and regroup when the time comes to vote to renew representatives of the Assemblée Nationale, the lower chamber of Parliament. #SansMoile7Mai (#CountMeOutOnMay7) is flourishing on social networks, notably among disappointed supporters of Mélenchon. In turn, militants and even politicians on the mainstream right have declared their intention to vote for Le Pen, a position that would have been unimaginable five years ago, and which confirms that Le Pen has a serious chance at election. In the aftermath of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election, it would be a grave mistake to think that Macron is guaranteed a win.

And yet: in spite of this dire prospect, the crisis France is currently facing holds an opportunity to do politics differently; the demise of the Socialist Party has also opened up a path for a more people-centered left. “Macron is no barrier against the Front National,” declared New Anti-Capitalist Party candidate Philippe Poutou; “the only solution against this threat is to take to the streets.” Poutou holds positions far left of the mainstream, but he expresses a drive to activism that drew attention throughout the presidential campaign. Whether or not this dynamic can translate into a popular, democratic, and humanist renewal of French politics will only become clear after May. No matter their outcome, these elections can only confirm how dire the current situation is.

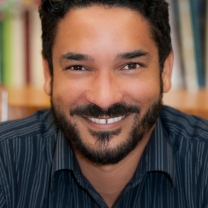

Grégory Pierrot teaches at the University of Connecticut. His research explores matters of race and nation in the Black Atlantic, including the Haitian Revolution and its global cultural impact. He grew up in the French city of Metz before moving to the United States.

Photo Credit: doubichlou14, "Feu aux bank macron le pen hors de nos vies!," via Flickr, 24 April 2017.