/ The Fabric of Scientific Discovery

Subscribe

/ The Fabric of Scientific Discovery

Subscribe

The Spoke continues its conversation with Wellesley College Professor Richard French, Louise Sherwood McDowell and Sarah Frances Whiting Professor of Astrophysics and Professor of Astronomy.

I think one of the lessons that is interesting for the Albright Institute—and I've been thinking a lot about this—is that on an international mission with diverse science goals, you learn very quickly that the equivalent of "America first" or "my science is better than yours" gets a little stale very quickly. So you need to develop the opportunity to collaborate and cooperate with people with whom you disagree, and to think carefully about the value of their arguments. And for me that was one of the long-term, lasting benefits of this mission; it was an inoculant against feeling that politics is everything, because in science, our ultimate goal was to learn as much as we could about Saturn. In political debates, it is not often that somebody says, "that's an interesting point, I've never thought of it that way -- I'm going to change my mind." By contrast, in science you're left in the dust unless you're willing to admit you're wrong and change your mind. So that, for me, has been a lesson that I like to convey to my students as well.

The Spoke: How does teamwork in science look like, since it is a skill that we want our students to learn?

Richard French: For me, one of the fun parts of this mission has been the collaborative part. In some ways, getting a Ph.D is described as a solitary endeavor. It's supposed to be "your research," but in practice, every paper that I've ever written of significance has collaborators. I choose those collaborators, and they choose me in part because each of us has different things to offer. Or, perhaps, because by collaborating we have enough time, by dividing the labor, to be able to get a complex task done. So I think one of the challenges of cooperating—when you're on a mission like this and you see all of the impressive people that you are working with, there is a tendency to think that you don’t have anything to offer. I think that this is an experience that students have, too—in the context of group work, they might think: "there are all those other smart students in my group, what do I have to offer?" A lesson from this mission is that everybody had something to contribute.

A metaphor that I don't particularly like, but it comes to mind at the moment, is if you're in a lifeboat and you're bailing, nobody criticizes you because you have a smaller bucket than somebody else because everyone recognizes that each contribution counts, and everybody can share in the success. A lesson I have learned is that we shouldn’t expect ourselves to be an expert in everything. Indeed, being okay with not being an expert in everything is a lesson that I've had to learn over and over again. In my collaborations I am grateful to my collaborators for recognizing that I can contribute, and I acknowledge that there are many things they do that I can't. I think that's a genuine lesson of collaboration.

Another thing that's interesting to me is the international nature of science. For instance, on my particular team, I have many collaborators from the mid-east. Among them, they speak five different versions of Arabic, and I have a lot of fun talking with them about Arabic slang, and what it's like in Jordan compared to Egypt, and Morocco. We all get along really well together and I feel that we are engaged in a larger enterprise than current political boundaries circumscribe. I think that sense of solidarity, and feeling that we're working on something that has a permanence and a legacy for future generations, is a way for us to rise above political differences. We simply don't discuss them. I'm sure that the Russians and Americans on the International Space Station are not mostly talking about politics, they're mostly talking about how they get the science out of what they're doing.

Collaboration on a project allows us time to work on something that brings out the best of the human spirit by working together. And what better way to realize that we're on the same planet, and everything that entails, than to take pictures of Earth from a billion miles away—and to see that there are no real boundaries between countries when you look from that distance.

The Spoke: How did the humanities help you consider and prepare for the end of the mission?

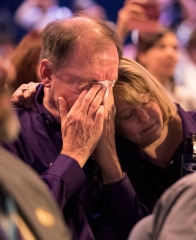

RF: Well, that's a very interesting question that is worth reflecting on. At the time of Cassini’s final moments, I was saddened by the approach of the end of the mission. I remember on Facebook, where scientists were posting about dreading the end, somebody responded: "it's just a freaking piece of metal." To this, I thought, "it's not the piece of metal, it's what the metal represents." It's the fact that I've been working with what feels like a family since 1989, sharing in the triumphs and disasters and calamities, the deaths, the new scientists joining us, and feeling that we're part of the continuous fabric of scientific discovery.

So I really did spend a lot of time thinking about the continuity of my own education, the advisors that I had, the ones that died too early. Carl Sagan was my first thesis advisor; I wish he had been alive to see these wonderful new discoveries of the solar system. I think the humanistic side, which, I think, many scientists have, was one of thinking beyond the question of: "what data will I not being able to collect next year because the spacecraft isn’t there?" Most of us weren't thinking about the fact that we hadn't discovered everything there was to discover about Saturn. Most of us were sad that the heady experience of working together on arguably the most successful space mission ever, at least in the solar system, was ending. It felt, for me, like somebody was telling me, "You had your last day at Wellesley College. No more office hours. No more students. You can't be with faculty anymore. You can't have a chat with the provost or the deans. You're never coming back." That's what it felt like. So I'm not surprised that I wept at that moment. The photo of me weeping went viral: now I know what the internet does. But I don't apologize for it, it's an emotional experience; Cassini has been a formative part of my life.

The Spoke: What has it been like involving your students in your research with the Cassini data?

RF: I love this question because I taught an upper level course about the Cassini early on in the mission. I had a handful of students taking that class and I was able to get data from some of the many instruments in the Cassini. For example, there was an article published in Nature about some infrared observations of Enceladus. I was able to call up my friend from a Cassini team and say "can you send me the data you used for that paper? I'm going to give that as a homework set to my students." So my students would do their own research projects using data that were not yet in the public domain. That was a lot of fun, and an upper level example of using the mission in the way you kind of expect.

But it occurred to me as I was participating in the mission that I had a very time-consuming set of tasks to do and I could, with help, write a program to analyze observations with student help. And I also had a big task, after the first four years of the mission, where we had seven different choices of sequences of orbits around Saturn and each team had to assess what those seven different orbital sequences would be like for their science. And I thought, I could involve some students in this work. So, students were involved in that project. It was great fun and I loved working with them. Over the years I have had the chance to involve a lot of students in the mission and, I think, these experiences for a science student are more than just another research experience. But for the non-science students, I think it had the opportunity to be transformational in the way of saying, "I didn't think I could do this, but I guess I really can." That's why I'm here at Wellesley.

Please join us next time for the third and last part of The Spoke's conversation with Prof. French. Part one, about Prof. French's involvement in the Cassini mission, is available here.

Photo Credit: "Chronicling Saturn's Northern Storm," via Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 25 February 2011.