As communities around the country work to procure COVID-19 vaccines for their residents during the ongoing pandemic, public officials like Liany Elba Arroyo ’98 and Wilma Chan ’71 are facing the challenges of vaccine distribution.

Arroyo, director of health and human services (HHS) for the city of Hartford, Conn., was as prepared as possible when the city reported its first case of COVID-19. Her team had been monitoring the spread of the virus; when it reached the U.S., they got together with local school districts, hospitals, and the federally qualified community health centers. “We had spent most of February updating our pandemic flu plan because that was the only playbook that we had—but we knew it was inadequate,” Arroyo said. “We knew that nothing like this had ever happened before. And how do you operationalize this plan?”

Now they are working to coordinate the vaccine rollout, and they have encountered obstacle after obstacle. Arroyo compares the situation to coronavirus testing in the state—“a lot of unknowns, a lot of shifting our tactics and strategy, a lot of partnerships.”

By applying for grants and seeking private funding, Arroyo said, Hartford’s HHS has secured sufficient financial backing to combat the virus, but money sitting in the bank does no one any good. “You have to hire people, you have to manage contracts. This is happening against the background of all of the work we normally do as a health department,” she said, such as treatment for HIV and tuberculosis. Arroyo and her team plan to integrate COVID-19 education for the community into their plans for the foreseeable future.

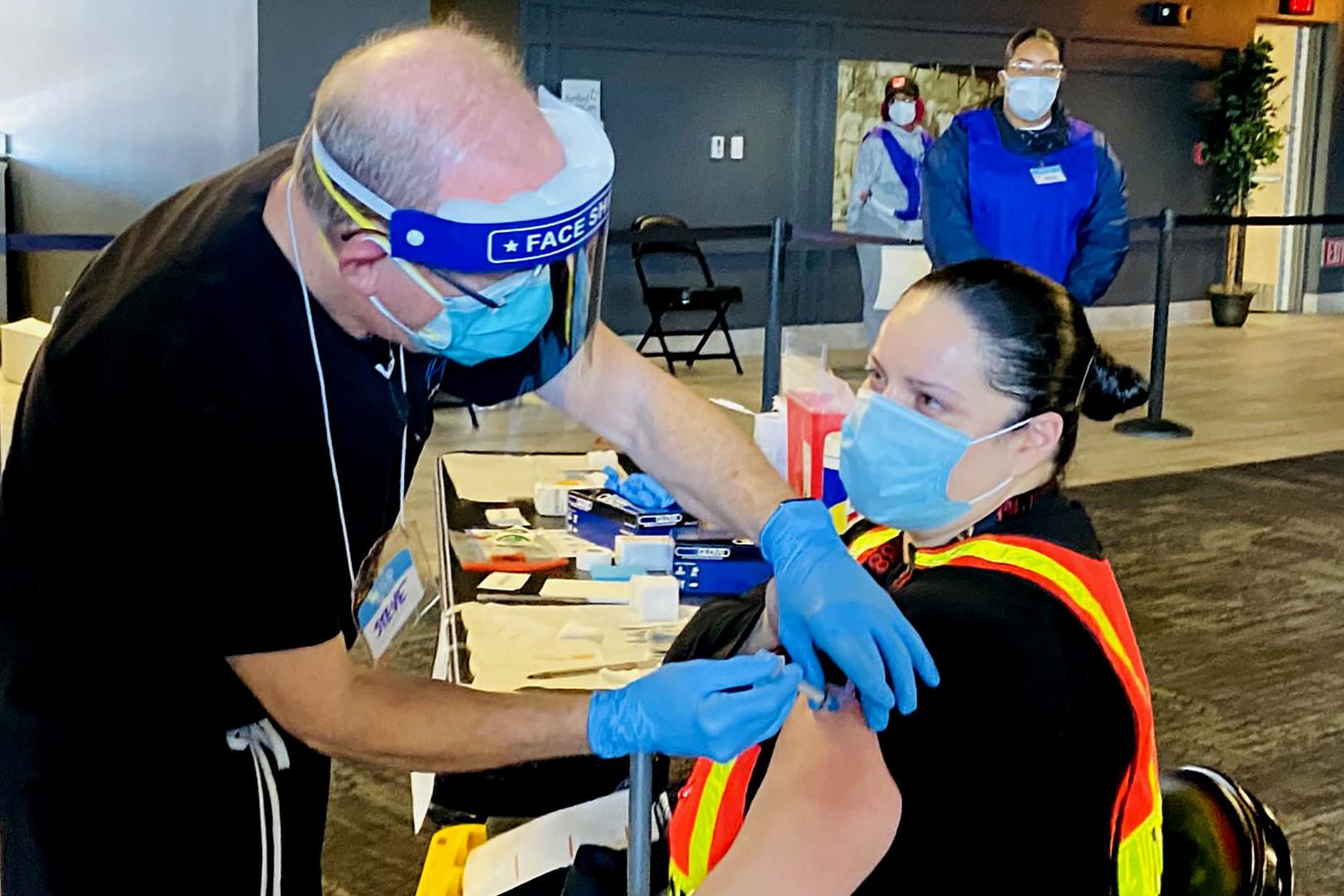

“I think the rollout overall—not just in Connecticut—has been rather inequitable,” she said, explaining that lack of English-language fluency, technological savvy, and transportation are the main barriers to access. HHS has vaccinated about 500 people during the last week of January, Arroyo said: “It’s a little drop in the bucket compared to what the hospitals are doing, but it’s a drop in the bucket of those that are the neediest.” Hartford, the state capital, is home to a population that’s 85 percent people of color, she said, and she stands firm about ensuring that the vaccine is available to communities hardest hit by the pandemic.

What drives her is personal and powerful: “I hold the work I do very close to my heart because I view the success that I’ve had coming from my own background—growing up working class, first-generation college student, first-generation graduate student, raised primarily by my mom and grandmother, who were factory workers—as a duty to give back,” she said. “It’s really important for me to ensure that people like me, and like my family, and like my neighbors where I grew up, have what they deserve—that they have what they need in order to lead successful lives.”

“There’s a lot of conversation about going back to normal,” she noted. “‘Normal’ is what led to the inequities that were exposed during the pandemic. And I would challenge that. Is going back to ‘normal’ really where we want to be? Is that good enough?”

On the other side of the country, in California, Alameda County Supervisor Wilma Chan ’71 is also pragmatic about the needs of her district. At the start of the pandemic, she attended training for contact tracing and arranged to give out stipends of $1,200 to enable people to stay home and decrease movement. “People felt that they had to go to work, but then they would come back and infect the whole family,” she said.

Though California has one of the single largest economies in the world, food insecurity is a problem in many areas and it has been exacerbated by the pandemic, so Chan made sure to set up a food distribution site in her county. “It’s shocking how many people don’t have food,” she said. She has also led an effort to implement a community-based approach to the crisis, working with organizations and clinics to combat vaccine hesitancy.

Chan criticized the previous presidential administration for not seizing the chance to obtain large quantities of the vaccine; as a result, she said, there will be no increase in Alameda’s supply until the end of March. For now, they expect to get only 14,000 doses a week—“not very much,” she noted, especially when the county hasn’t yet vaccinated everyone in the first tier.

Alameda officials know how many doses the area has received, she explained, but there’s no centralized infrastructure or database. “People will call and ask, ‘What’s wrong with the county?’ Expectations have been raised beyond the production rate,” Chan said. A report from the Alameda County Public Health Department states the fact in stark terms: “The pace of implementation continues to be constrained by vaccine supply.” Compounding this difficult situation, California’s guidelines for distribution keep changing, she said. Beyond phase 1-A, which includes hospitals, long-term care facilities, community health centers, and pharmacy staff, among others, the priorities have remained uncertain.

Chan celebrates her 50th Wellesley reunion in June, and reunion events this year will be virtual. She expects to be combating COVID-19 and the accompanying fallout through the summer months.

She added that the apportionment of federal money last year was essential, and said it’s imperative that Congress pass a COVID-19 relief bill. Now that the Senate has backed a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package, she has hope that more help will come soon. Despite the considerable logistical ordeals, Chan’s overwhelming feeling is one of gratitude: “It’s wonderful that the vaccine is here.”

This is the first in a two-part series looking into how Wellesley alumnae are involved in the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine.