Wellesley Biologist Studies Oceans’ Smallest, Most Abundant Photosynthetic Organism

Two hundred meters below the ocean’s surface is a thriving world of phytoplankton, microorganisms that processes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and turn it into oxygen.

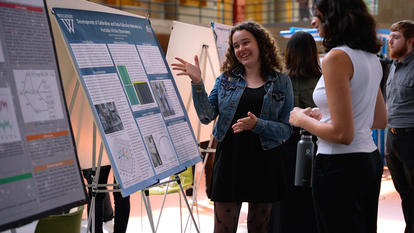

A research team including Steven Biller, assistant professor of biological sciences at Wellesley College, has uncovered the critical role the microscopic photosynthetic organism Prochlorococcus plays in this process.

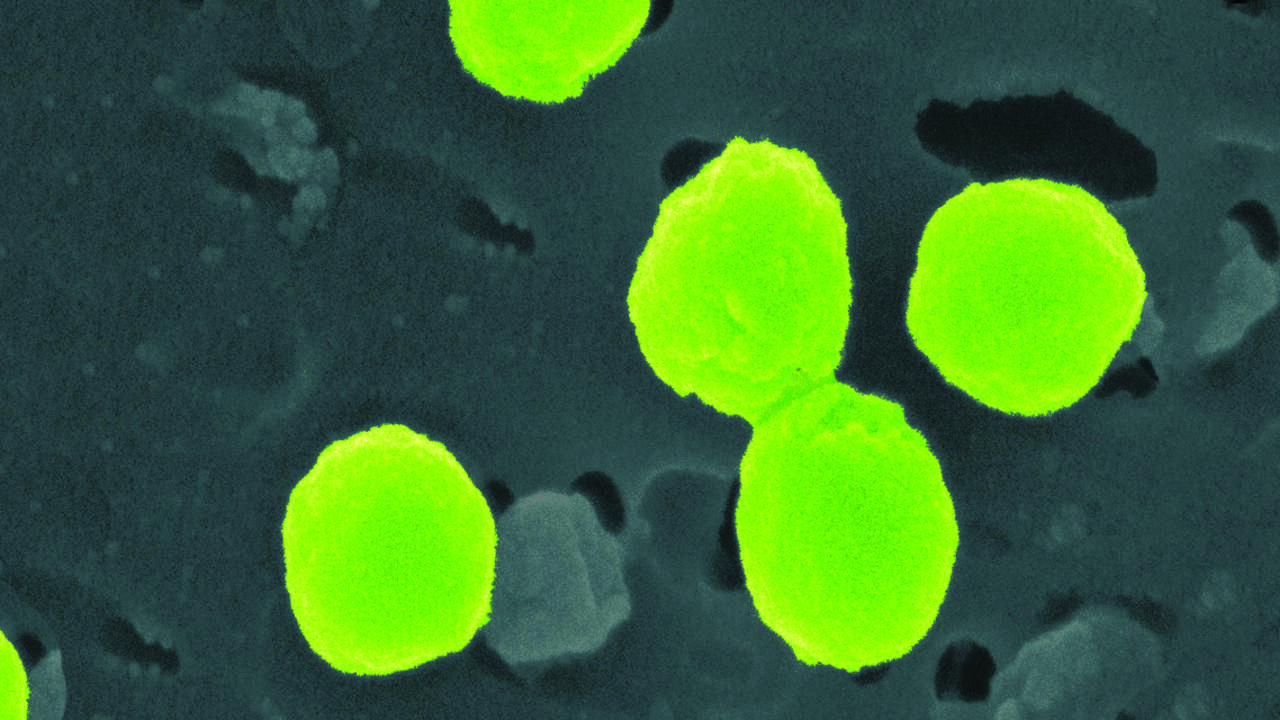

Prochlorococcus, which was discovered 30 years ago, performs photosynthesis by using the sun’s energy to release oxygen from a water molecule. Invisible to the naked eye, the bacteria is collected in ocean water samples.

Biller, who recently joined the Wellesley faculty, and two other marine biologists described their research for a recent blog post of the National Public Radio program “Science Friday.”

In the laboratory, scientists have found that Prochlorococcus thrive when other cells are present. “When Prochlorococcus is growing just by itself, it doesn’t grow as quickly, at as high of a density, and they’re much more susceptible to various kinds of stresses and perturbations in the lab,” Biller told NPR. “So they actually really like having these other cells around.”

From this characteristic, Biller said, scientists learned about the interplay between microorganisms within the microscopic marine community, and found that Prochlorococcus is responsible for moving and delivering all kinds of molecules—lipids, proteins, and other fragments in the ocean.

Prochlorococcus lives in an underwater environment called the ocean’s “invisible forest.” “This is what’s happening in the open ocean—but instead of trees, we have these single-celled photosynthetic organisms that you just can’t see if you look,” said Anne Thompson, a biological oceanographer who collaborated with Biller on this research.

Scientists have predicted Prochlorococcus would remain generally stable in warmer waters but have not determined how they’d be affected by climate change overall.

Photo: A pseudo-colored image of Prochlorococcus seen under the microscope.