The People’s Republic of China at 70: How Chinese Literature and Cinema Illuminate the Cultural Revolution and Its Aftermath

On October 1, the Communist Party of China marked the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China with a series of commemorative events across the country. In Beijing, President Xi Jinping presided over a massive parade held to honor the victory of Mao Zedong’s Communist Party over nationalist forces and the establishment.

We asked Mingwei Song, associate professor of Chinese at Wellesley and an expert in modern Chinese literature, film, youth culture, and intellectual history, to share his thoughts on the significance of the anniversary, the ongoing protests in Hong Kong, and how Chinese literature and cinema reflect the current state of cultural production in the country.

Q: How has the Chinese Communist Party’s attitude toward the cultural revolution changed over the past few decades? Has the shift been reflected in Chinese literature and film?

Mingwei Song: Defining the Cultural Revolution as a national predicament made it possible for China’s reform to begin 40 years ago. Scar literature, a genre of Chinese literature that emerged in the wake of Mao’s death that portrays the suffering of intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, the root-seeking literary movement that emphasized local and minority cultures, and the fifth-generation filmmakers who brought Chinese cinema abroad were all the result of the thaw on creative restrictions that happened throughout the early 1980s. Today, however, under Xi Jinping, many recent films and novels exposing the dark side of the Cultural Revolution are banned. Xinhua News Agency’s two recent conflicting statements regarding the Cultural Revolution also tell us a lot about the current leadership’s attempt to glorify Mao’s legacy as well as the Cultural Revolution; one of the statements redefines the Cultural Revolution as an experiment, downplaying the tragic side of Mao’s revolution.

Q: What do the protests in Hong Kong suggest about the Communist Party’s ideological and cultural hold on the people of China? Do the protests represent a minority view, or is this sentiment manifested on the mainland as well?

Song: The protests in Hong Kong have perhaps strengthened the Communist Party’s ideological hold on the entire nation. These protests represent the thoughts of the people of Hong Kong, but the Communist Party is obviously worried about their influence on the Chinese population on the mainland.

Q: How is protest against the Communist Party represented in contemporary Chinese literature and film?

Song: In literature and film, there are very few works representing protests, unless they represent much older protests mobilized by the Communist Party against the nationalist regime before 1949. One of the very few films about the 1989 Tiananmen protest, Summer Palace (2006), was completely banned in China.

Q: You’ve written that the “rise of youth” is among the most dramatic stories of modern China and is manifested in contemporary Chinese literature, especially through the bildungsroman. What novels offer insight into this modern China?

Song: Most of the bildungsromans I studied in my first monograph in English, Young China, are very long and not available in English translations. One particular novel that is available in English translation, Rainbow (1932), is a bildungsroman about a young woman breaking up with her traditional family and trying to engage with political activities. Her bewilderment about the conflict between the individual and revolution highlights a perpetual theme in the Chinese bildungsroman regarding self and society, a conflict between the freedom and formlessness of youth and the disciplines imposed on youth.

Q: What can the renaissance in Chinese science fiction in the early 21st century teach us about the state of cultural production in China?

Song: This new wave of Chinese science fiction could exist under the Chinese government due to the relative lack of attention paid to it. Between 1999 and 2010, most of the important works by this new generation of science fiction writers were already there, but nobody but fans of science fiction knew about them. After the new wave became a national sensation when The Three-Body Problem gained a global readership in 2014–16, the Chinese government tried to appropriate this new wave to achieve its own goals, such as promoting space programs and popularizing the sciences. However, with this sort of attention, the new wave lost its momentum.

Q: What cultural product would you recommend to an outsider who wanted to gain greater insight into life in China in the 21st century?

Song: “Regenerated Bricks” by Han Song is an interesting science fiction story that seeks the deeper “truth” behind China’s economic miracle. This is a poignant story about the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, about how China’s later economic development has been based on a low-tech invention called “regenerated brick,” which contains the remains (and souls) of the victims of the earthquake.

The film Kaili Blues directed by Bi Gan focuses on rural areas in China’s southwest. The ordinary life of the local town-folks is turned into a dream-like narrative about betrayal, murders, memory, and forgetting. The film achieves artistic sophistication in many ways, including a long take that lasts 40 minutes, which challenges our conventional concepts of time, space, and reality.

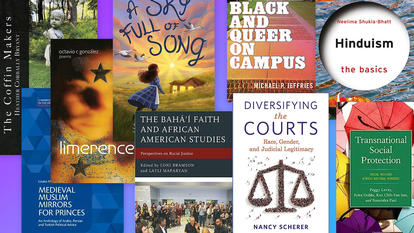

Photo: Chinese tourists wear 70th anniversary t-shirts as they stand near a large screen set up for the 70th National Day celebrations while visiting Tiananmen Square in Beijing. China marked the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 on October 1.