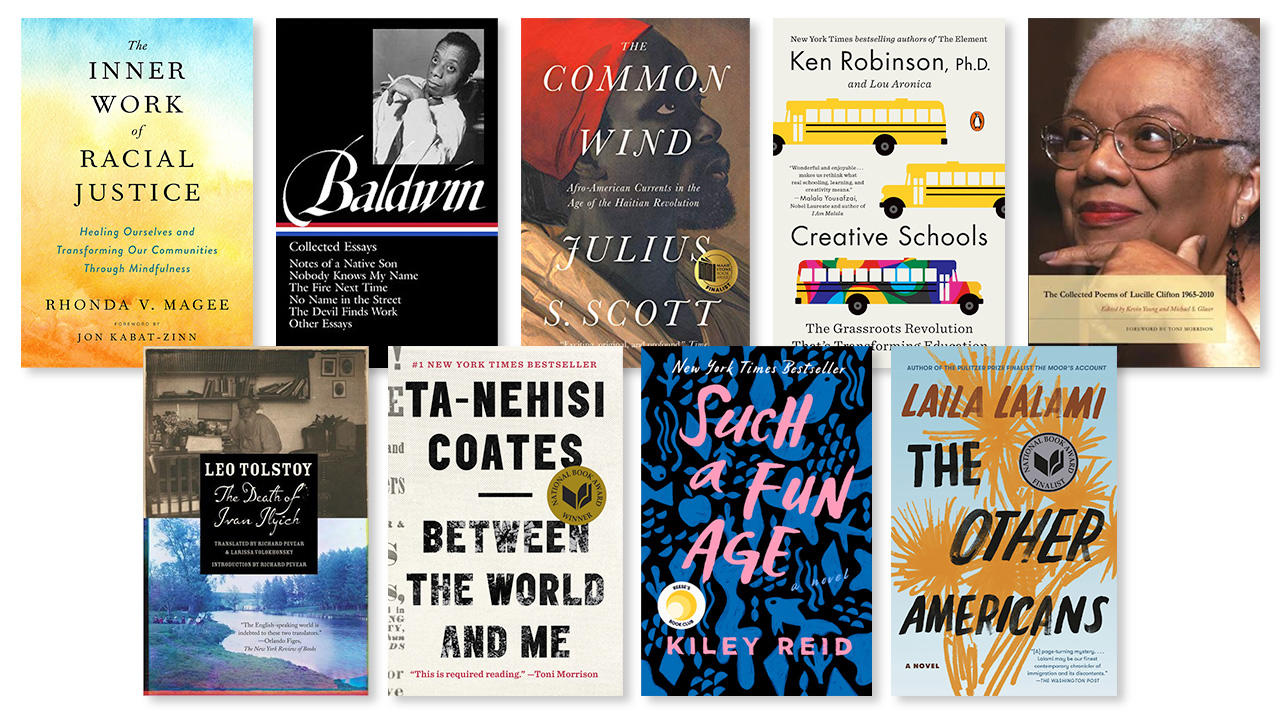

What Wellesley Faculty and Staff Are Reading During a Summer Like No Other

During times of political, social, and economic upheaval, books can be incredible sources of illumination and interrogation of institutions and personal experience. They can also be powerful engines for personal connection and growth. As James Baldwin said, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

As the pandemic intensifies in much of the country, and as protests against social and racial inequities continue, Wellesley faculty and staff share the fiction, nonfiction, and poetry titles that have been resonating with them in this unprecedented moment.

Jennifer Chudy, Knafel Assistant Professor of Social Sciences and assistant professor of political science

I recently finished Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid. Set in present-day Philadelphia, the book depicts the story of a young Black babysitter named Emira and her white employer, Alix. Reid presents a vivid portrait of how some liberal white people think about race, describing in great detail the elaborate mental gymnastics they can employ. In the process, the white characters in her book often burden Black people as they seek to justify their questionable actions. The result is funny and cringeworthy and displays the harmful limitations of supposedly good intentions.

Oscar Fernandez, Class of 1966 Associate Professor of Mathematics and faculty director of the Pforzheimer Learning and Teaching Center

Ken Robinson’s Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That’s Transforming Education unpacks the industrial structures underpinning schools today (e.g., standardization) and lays out a new vision for education “based on a belief in the value of the individual, the right to self-determination, our potential to evolve and live a fulfilled life, and the importance of civic responsibility and respect for others.” This vision resonates with me, not only because I strongly believe these are better founding principles for education, but also because it reimagines education in ways similar to what Wellesley will be attempting to do this fall, an effort I am a small part of via my work with the PLTC.

Octavio González, assistant professor of English

I recently read Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, a great meditation on illness and death, which tracks the life of a late-19th-century man in urbane, bourgeois Russian society. During the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown, I found it exceedingly difficult to do what academia and American culture demands, the same demands Ivan Ilyich takes to heart: Produce, earn, buy; rinse and repeat. This short novel was all the attention span I had at the start of this long siege against life that we call the pandemic.

As the police brutality against Black Americans became more visible, and Black Lives Matter protests spread, I saw the spark that Ivan Ilyich saw at the end of his life: People no longer living life as it’s “supposed to be lived,” that is, as a way to accumulate possessions and prestige, while conforming to the inequities that govern our social world. The explosion of activism against anti-Blackness showed how life is supposed to be lived, by forcefully confronting the forces (and agents thereof) that violently repress Black lives as America’s police-state status quo (defending the lives of the Ivan Ilyichs of our world).

How to resist this mandate to produce and reproduce like good (white or white-adjacent) social actors is the question that comes next. For me it is by reading stories like Tolstoy’s, and teaching and writing about the issues that matter: issues like HIV/AIDS as a precursor to this pandemic, which showed how governmental incompetence and active, pseudo-Christian anti-queer and anti-Black hostility facilitated countless deaths.

Lidwien Kapteijns, Elizabeth Kimball Kendall and Elisabeth Hodder Professor of History

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me addresses his teenage son in a moving personal account and historical contextualization of “[w]hat it is like to inhabit a Black body and find a way to live within it” in the U.S. To Coates, the destroyers of Black lives are not bad apples but individuals who correctly interpret and live up to their country’s history and legacy. He cannot reassure his son that things will be all right, but he warns that “the quest to believe oneself white” blinds others to their own vulnerabilities, which, in 2020, under Trump, are all too obvious.

Layli Maparyan, executive director of the Wellesley Centers for Women and professor of Africana studies

I’ve been reading Rhonda V. Magee’s book, The Inner Work of Racial Justice: Healing Ourselves and Transforming Our Communities Through Mindfulness. Lately, I’ve been intensely interested in how people are thinking about bringing spiritual resources to the project of racial justice. In her book, Magee, an African-American law professor who also happens to be a nationally recognized mindfulness expert, interweaves personal narrative about how meditation has helped her survive, overcome, and transform racial injustice with deep insights about how a mindful orientation opens up new pathways for eradicating systemic racism. With frequent “how-to” sections, this book is eminently actionable.

Anjali Prabhu, Margaret E. Deffenbaugh and LeRoy T. Carlson Professor in Comparative Literature

I have recently turned to James Baldwin’s writings for inspiration, guidance, and comfort and been just delighted by his intellectual and artistic range, his compassion, and his talent. I could pick one of his books, but I want to bring attention to something else because I’ve also been listening to whatever I have found of his voice online. His public conversation with Nikki Giovanni (1971), which is available in two parts here and here, is an exquisite exchange between two brilliant minds across generations, talking about America, about what it means to be Black, about inequality, about the fulfillment of our humanity as individuals and as a society. They said it all…and they model how a conversation filled with gentleness and love can tackle the most brutal of questions. Every young person should listen to that conversation, no matter who they are or in which part of the world!

Antonio J. Arraiza Rivera, assistant professor of Spanish

I’m reading The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution, Julius S. Scott’s powerful account of how Black communities in the 18th-century Caribbean combated slavery through networks of communication and solidarity. The Common Wind shows how resistance to and emancipation from state-sanctioned violence were achieved by men and women who recovered their freedom and settled in towns and cities, shedding light on how collective action leads to transformative change. It also invites readers to think about how history gets written, and whose voices are, and should be, heard.

Pamela Taylor, assistant provost of institutional planning and assessment and director of institutional research

The book that has been resonating with me is The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965–2010. What I love about this collection is how much of the historical struggle of Black people is chronicled in Clifton’s poems—lynching, James Byrd’s murder, the Birmingham church bombing, Rodney King, and Nelson Mandela’s release. She weaves past and present, centering this history in the experience of a woman/mother/daughter/poet/cancer survivor. Her words are solace, balm, protest, hope, and peace all in one.

Eve Zimmerman, director of The Suzy Newhouse Center for the Humanities and professor of Japanese

Laila Lalami’s 2019 novel The Other Americans resonates with the current moment. Lalami spins a gripping mystery around the hit-and-run death of a Moroccan-born restaurant owner in small-town California. Told from multiple perspectives, by the man’s daughter, a police officer assigned to the case, and the man and his wife, among others, we see a brutal murder through a prism. Who qualifies to be an “American,” Lalami asks, and who does not? Who is afforded the rights and privileges of citizenship, and who is not? In the form of a suspenseful page-turner, Lalami challenges her readers to think, drawing them into the heart of the book’s secrets. It’s thoroughly satisfying, good fiction.