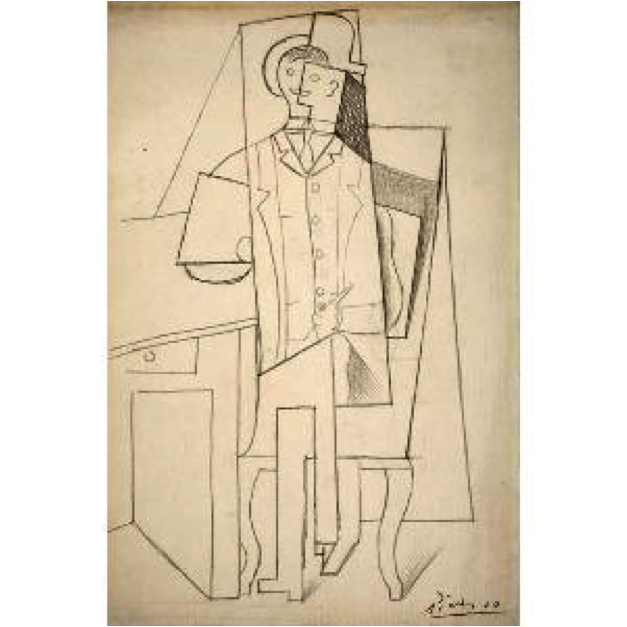

Man with Pipe

1959.47

Over the course of his nearly 80 years of prolific production, Pablo Picasso made more than 20,000 works of art in a range of mediums including painting, ceramics, sculpture, and stage design. In addition to his numerous masterpieces, Picasso is perhaps best known for his pioneering invention of Cubism along with the French artist Georges Braque. This groundbreaking movement marked a radical shift in modern art and was adapted by many painters into a number of influential artistic styles. Picasso himself worked in a range of visual modes and styles throughout his career, using the techniques and forms he felt were best suited to the particular idea he was trying to express. Of his stylistic diversity, he stated simply, “Whenever I wanted to say something, I said it the way I believed I should.”

Nowhere is the strength of Picasso’s interest in experimentation more evident than in his varied explorations of Cubism. Questioning the very formal qualities of painting, Cubism rejected traditional ways of representing three-dimensional surfaces on two-dimensional canvases. Since the Renaissance, artists had depicted objects and figures in deep space, using conventions of light and shadow to show them from one perspective at a single instant in time. Cubism abandoned the single viewpoint and rendered the subject as a set of overlapping planes set in narrow space. The resulting canvas had the effect of being broken, then reassembled in a disjunctive manner, so that each fragment reflected a different vantage point.

In Man with Pipe, Picasso used Cubist methods to portray his subject within an interval of time and space; the man’s face, for instance, is a composite of frontal and profile views, giving the impression that he turned his head at some point during the perceived moment. Meanwhile, shadows created by the legs of the easel imply a single viewpoint that is contradicted by the placement of other objects in the scene. This impossible configuration of objects reflects Picasso’s desire to translate the visual experience of looking at something onto a two-dimensional surface. In contrast to many of the artist’s completed Cubist paintings, this drawing is fairly representational; the figure and the surrounding furniture have been abstracted into predominantly geometric forms, but recognizable signs such as a man’s vest buttons and a desk drawer identify familiar objects and figures. Nevertheless, its attempt to relay the continuous and multilayered experience of viewing such a scene is decidedly Cubist, as are the jutting forms that deny traditional conceptions of three-dimensional space.

Emily Zhao ‘17

Curatorial Summer Intern, Davis Museum, 2015