Our Places Our Voices Winter 2020

Common blue violet (Viola sororia) is one of several early spring blooming plants found on our campus landscape. Keep an eye out for this flower as spring arrives and record your observations in iNaturalist. Your observations will become part of the Paulson Ecology of Place Biodiversity Project. Photo: Sandy Wolkenberg

Spring peepers (Pseudacris crucifer) are small, round frogs with a dark mask and a faint cross on their backs. In the spring they make a loud, high-pitched peeping call to attract a mate. Become a citizen scientist and download the iNaturalist app and record when you first hear them calling (you can even upload a recording so the observation can be confirmed by other naturalists!). Photo: Jenn Yang '12

Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris) is an early spring blooming plant with beautiful yellow flowers. Plant flowering times in spring for this and other common wildflower species have increased near Walden Pond in Concord, MA by about one week over the last 150 years. Photo: Suzanne Langridge

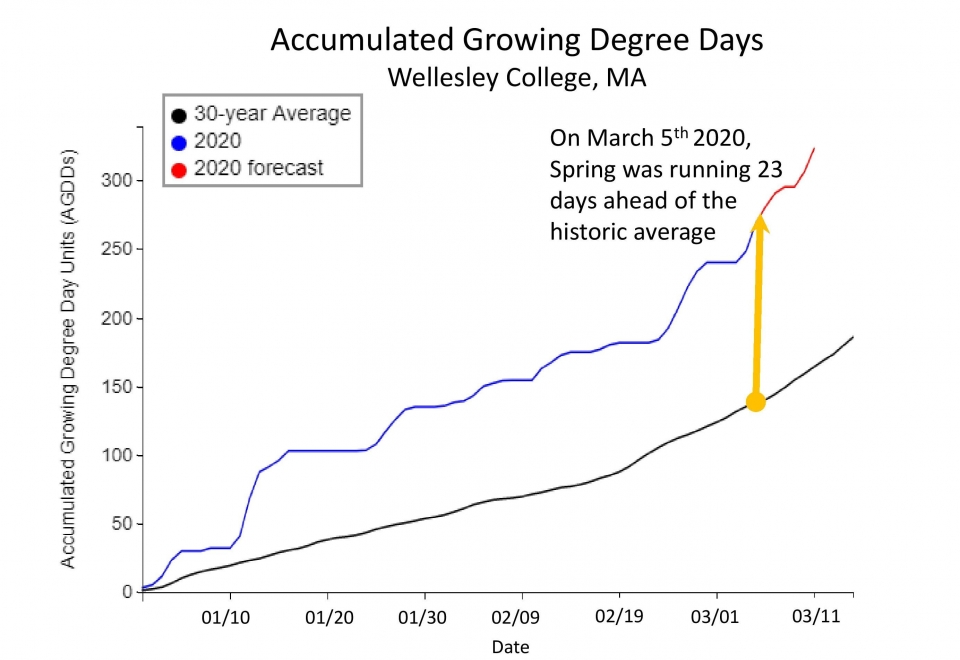

Accumulated Growing Degree Days (AGDD) are an index of heat accumulation that drives phenological activity. Many species respond by leafing, flowering, or emerging at particular heat accumulation thresholds. This graph, developed using the National Phenology Network data visualization tool, illustrates how the 30 year average AGDD (black line) differs from 2020 (blue line - with red forcasted) at Wellesley College. Wondering how fast it’s warming up in your hometown? Enter your zip code here to find out.

First bloom, singing frogs, and a changing landscape: how do mild winters impact the natural environment at Wellesley?

“We may not even see the bare ground, and hardly the water, and yet we sit down and warm our spirits annually with this distant prospect of spring.”—Henry David Thoreau, 2 March 1859

Students return to Wellesley in January, expecting to encounter a brutal New England winter, but this year students found themselves revelling in warmer temperatures that contributed to the third warmest January on record in Greater Boston - with a record high of 74 degrees Fahrenheit. Many welcomed the mild weather as they walked to class - and yet some miss the snow and a frozen Lake Waban, and wonder how these changes impact our local natural environment and our sense of place at Wellesley.

Temperature is a climatic cue that impacts the timing of biological processes of plants and animals (also called phenology) -- like growth, reproduction, and senescence (dying). In Wellesley, cold winter temperatures gradually give way to warmer weather, signalling the start of spring and the emergence and return of countless species from their winter retreats or domancies. One way that plants and animals can respond to climate change is by shifting the timing of these biological events.

Just up the road from Lake Waban at Walden Pond, Henry David Thoreau, a 19th century naturalist-writer, faithfully journaled changes in New England phenology on his regular walks around the Pond. His detailed notes on first spring flower blooms, among many other close observations, provide a rich historical record that researchers used to understand how climate change is impacting phenology. Researchers compared first bloom dates of many early flowering spring plants we see on campus, such as marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), pink lady slipper (Cypripedium acaule), and violets (Viola spp.), from Thoreau’s journals and from other “citizen scientists” near Walden Pond to current observations and found that these plants were blooming on average about one week earlier.

Shifts in phenology with more mild winters include not just earlier flowering times, but also changes in when plant leaves emerge and animals begin to sing, these shifts can lead to complex changes in our environment. In another study using Thoreau's and other citizen scientists' observations, researchers found that trees near Walden Pond were leafing out two weeks earlier, shading out wildflowers and impacting their growth. On Wellesley's campus, Katherine Brainard, Post-Baccalaureate Fellow at the Wellesley College Botanic Gardens, noticed several plant species budding in January and February this year. “The lilacs were breaking leaf bud in January following the record warm temperatures. This is extremely early. Many bulbs were emerging from the ground in January, which is also extremely abnormal for this zone.”

Adam van Arsdale, Associate Professor of Anthropology, has spent the last 13 years “engaging with outdoor spaces on a daily basis” and has “become more aware of the changes from season to season and year to year.” including noticing “when the spring peepers and tree frogs are active, or when the skunk cabbage first begin appearing, or when the ferns emerge, in a way that I never have previously.” For this reason, he was alarmed when he heard frogs calling in January - usually not heard on campus until mid-March or April.

On Wellesley’s campus we can take up the mantle of Henry David Thoreau and become citizen scientists as we walk around Lake Waban or through the Botanic Gardens, taking note of plants and animals we see and hear.

Unlike in Thoreau’s time, we now have the ability to record and upload our observations to iNaturalist, a citizen science platform that includes a network of naturalists who will help identify what you see and hear. When you upload your observations of the first flowers you see or recordings of frogs you hear on the Wellesley campus it becomes part of the Paulson Initiative Biodiversity Project on iNaturalist. This information can be used by our campus community and by scientists around the globe to understand the impacts of climate change on plant and animal species. Together we can work toward a better understanding of our natural environment, and by doing so become more in tune to our own connection to the world around us.

Dan Chiasson on the Changing Poetry of Place

As told to Paulson Intern Matilda Burke '21

Can you talk a little bit about the tradition of poets writing landscape and how that’s developed over time?

We are confronted with an incredibly beautiful, powerful natural world, and it’s always been poets’ challenge to bring it into language somehow--and when you do that, you make meanings. So you’re confronted with some frightening spectacle of a storm, or some beautiful spectacle of a sunset--how are you going to describe it? What forms are you going to use, what vocabularies are you going to attach to it? All of this has been one of the oldest imperatives for poets.

I think what’s different about for a poet, rather than, say, a landscape painter--you know, a landscape painter, if they’re a realist, can depict what she sees. A poet, by putting it into language, is converting it into a completely new system and by doing so, suddenly automatically attaching meanings to it.

Which landscape poets do you think are most relevant today?

Well, I’ve been following a resurgence in landscape poets who are really quite cognizant of climate change. There’s a writer named David Baker that I think of as sort of anti-pastoral: he writes about ways that the landscape is being ruined or squandered. He’s also very conscious of year-over-year change. He’s a guy living in Ohio, in a rural part of Ohio, and he has been looking at the same landscape year after year after year, and his testimony is quite important--that this landscape has changed, and that the seasons have changed, and that the seasons are breaking through in different ways that are unsettling, frightening. It’s changing the ecosystem there.

There’s a poet named Tommy Pico that I reviewed a couple of weeks ago in the New Yorker who is Native American, raised on a reservation outside of San Diego, and he has a volume called Nature Poem. It’s about some of the ways that writers of color have grappled with entering this tradition, which is always--in America, anyway--coded as rather white and patriarchal. But Pico is writing from and changing this tradition--he’s trying to find his own place meanings in nature, in his complex process of embracing and resisting the tradition of nature writing.

Sumita Chakraborty, a graduate of Wellesley--class of 2008 or '09 I believe? Has a new book coming out, Arrow, from Alice James Press this coming fall. There's a real grieving for the world in that book. The poet Robyn Schiff just read some absolutely amazing lines from a new, long poem, to an audience at an event at Yale. Scary lines about being alive now in this emergency.

I feel like landscape poetry--if you go back to Robert Frost, for example--Frost was working out these existential and philosophical questions by writing about the landscape. What is the place of the human, the individual human, when faced with this great, annihilating, totally unsympathizing, impersonal reality that surrounds us? So: loneliness, grieving. His work is absolutely amazing, and I teach him to this day, he’s one of my favorite poets--but: contemporary writers have started to think less about the fate of the human within the landscape and more about the landscape itself. We always took for granted that when we died, there would be a world that would carry on, and there was the poignancy; but I don’t think that that’s something we can be that confident in anymore. The signs are bad.

As a New England writer yourself, how do you fit into--or break with--all of this?

I grew up in Burlington, Vermont--certainly we were surrounded by the beautiful lake, and the mountains, and so on, but I never found that I wanted to write about nature--it wasn’t what was on my mind, I had other subjects. Over time, probably by moving away from Vermont and reengaging with it in my memory and imagination,, I’ve become extremely fixated on the natural world of where I’m from.

I’ve got a new manuscript called The Math Campers--I’ll just tell a quick story about it. I was imagining this town in Vermont, Greensboro, a beautiful town built around Caspian Lake. I was imagining this summer camp for math geniuses. They all turn up there and are falling in love and having all of these teenage experiences that they fear will soon end; so they conspire to--using math alone!--prolong the summer, to make the summer endless.

As I was writing, I realized--oh my god--this whole iconography of a summer that spills over into the fall is now terrifying, it’s very frightening. I was trying to create this almost idyllic idea, but I had to grapple with the fact that all of the imagery used for a very mild autumn, which is what the kids are imagining they can pull off, is very scary.

As a person who is now writing--in my own way--nature poetry, I think the upshot of some of the metaphors has changed. John Keats has a poem, “To Autumn,” which takes a very sympathetic view of autumn. Keats thinks of autumn as this poor entity or phenomenon--very human--that has not as much fame or celebrity as spring. He’s comforting autumn, and he has a number of images of a very mild autumn: images of bees, and of flowers, and of all these things prolonged beyond their natural interval or span. It’s unbelievably beautiful when you’re thinking about Keats’s own mortality--he’s thinking about when he will die; but now when I read it, I think about climate change. So the realities of our contemporary, fearful moment are definitely seeping into the meanings, even of past poetry.

On that note, how have you seen the landscape--particularly here at Wellesley--change over the years?

It’s February, and it’s 60 degrees--I have my office window open!--and you know, somebody might say “Well, that happens every year, or it’s intermittent, or there’s no pattern, or the trend year-over-year is not troubling,” but it is. We can still trick ourselves, on any one day, into thinking “Ah, a 60 degree day in February, what’s better?” I’m in a great mood today, I’m in an incredible mood because of the weather, but what we’re saying now--is this a harbinger of something really terrible? So in this landscape, yeah, it pains me to see all the rhododendrons budding in March when you know that two weeks down the line, there’s going to be a deep freeze. There’s just something deeply anxious about the change of seasons now--even the iconic winter thaw, the arrival of the first few flashes of color. We’re off balance, indebted. It’s like living in fear of a creditor.